INVESTMENT CONCLUSION

The UK housing bubble is a myth. Current price declines are principally function of Brexit-related uncertainty. While you’d have to be mad to buy until this fog lifts, this means there is pent-up demand to stabilise the market on a smooth transition out of the EU. The risk of a hard Brexit is inherently bad: it would likely lead to a broader economic recession and house price slump. But even then, we think misunderstood housing fundamentals mean fair value is higher than the doomsters suggest and would look to buy UK residential real estate on the first sign of economic stabilisation.

ANALYSIS

Ever since the 2016 EU referendum, the UK housing market has been slowing. Unsurprisingly, the deceleration was led by London, where price rises had outstripped those of the rest of the UK by a large margin, matched only by some idyllic pockets of the south east commuter belt. The UK’s ‘housing complex’ rose in tandem with prices, taking the blame for all manner of social and inter-generational problems.

Critics were quick to attribute rising prices to the buy-to-let phenomenon and a shortage of housing stock – a function of nimbyism (not in my backyard) which restricted access to development land, preventing the building of ‘much needed’ new homes. But these factors seem to be significantly exaggerated when looking at the data.

Real expensive, or not?

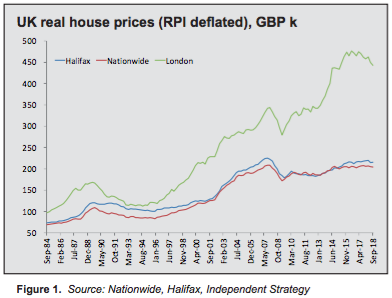

The focus on the level of real house prices is the classic example (Figure 1). One can’t dispute that the price of a house has risen sharply in real terms. But housing is not priced off inflation rates, or even wages. The price is built on the cost of acquisition and the mortgage repayments (cost of capital) that need to be made to remain in situ and pay down the debt outright. How expensive they are relative to a tin of beans is entirely irrelevant.

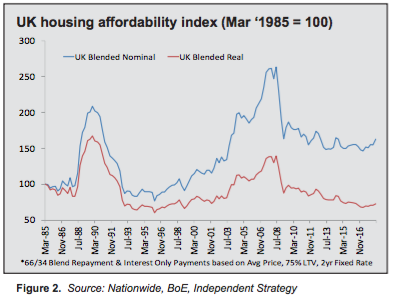

Looking at simple affordability, housing only looks expensive in London. And even then, it’s still below the levels seen at previous peaks, notably the late 1980s boom and coming into the global financial crisis (GFC). Indeed, for the UK as a whole, affordability matches the levels seen in the mid-1990s, when housing was cheap (Figure 2). That’s despite a doubling of house prices in real terms since then. So what gives between the narrative of priced-out ‘generation rent’ and the parallel reality of reasonable affordability?

Crisis frictions & political solutions

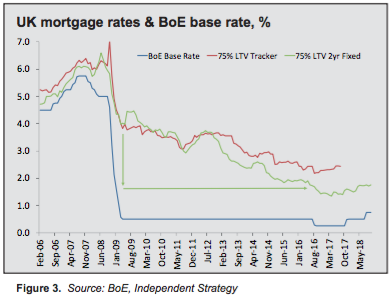

A good chunk of this is psychological and comes back to the GFC and the drop in house prices that followed. Like all assets, those that depreciate lose favour and the gloss housing had running into the boom (and had again until the Brexit vote) rubbed off. Tied up with shrinking credit availability, via the death of 100% – and even 110% – mortgages and generally sticky lending rates (Figure 3), it was perceived to be a bad time to buy.

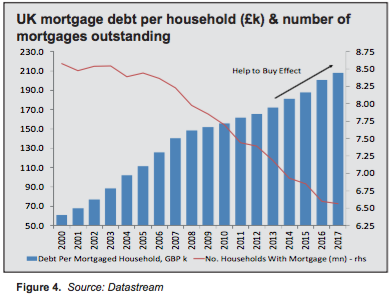

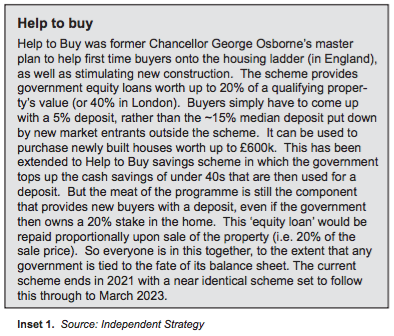

The price boom only resumed when the Bank of England (via its Funding for Lending programme) and then the government (using “Help to Buy”, Inset 1) tried to rekindle demand. The latter scheme did so to excellent effect. House prices were immediately marked up, reflecting the impact the government’s equity contribution would have on purchasing power, and continued to rise until the start of 2016.