One of the great things about most real estate is the relative predictability of cashflows and rental growth due to multi-year contracts (and the importance of the physical property to the tenant and frictional costs of relocating).

The lower cashflow volatility means real estate is considered as lying somewhere between fixed income and equities within the financial asset spectrum.

When considering the valuation of financial assets, there isn’t the typical utility one derives from owning art or other physical assets where there is often consumption in some form – i.e. fine wine / whiskey, rare sports cars, precious metal / gem jewellery. The utility aspect is less formulaic and therefore value is not easily derived mathematically, especially given that the desirability varies from person to person. Given the payment is fiat currency, the utility may also depend on the individual’s willingness to spend and is linked to how well-off they are and what other competing uses they have for cash.

In recent decades, non-financial assets are increasingly seen as investments in their own rights… that is, the acquirer considers not only the utility it would bring to them, but also how desirable it would be to other future investors / consumers. This involves some second guessing of what the marginal buyer may pay for an “asset” in the future and is nothing new – the Dutch tulip mania of the 17th century is a classic example, while a plethora of crypto assets including Bitcoin are modern examples.

Therefore, as much as the pricing of financial assets is formulaic (because the primary objective is to maximise return for a given level of risk), the pricing of non-financial assets involves more arbitrary factors that are not formulaic.

Both types are subject to assumptions about the future, but financial assets are a means to an end, and not the end in itself. Financial assets are also commoditised; that is, you can sell an equivalent amount of Apple shares or bonds to buy the stuff you really want. Valuing fixed income securities is the most objective given the highly structured mathematical approach; real estate and equities carry assumptions that are more subjective but valuing them is not as difficult as non-financial assets.

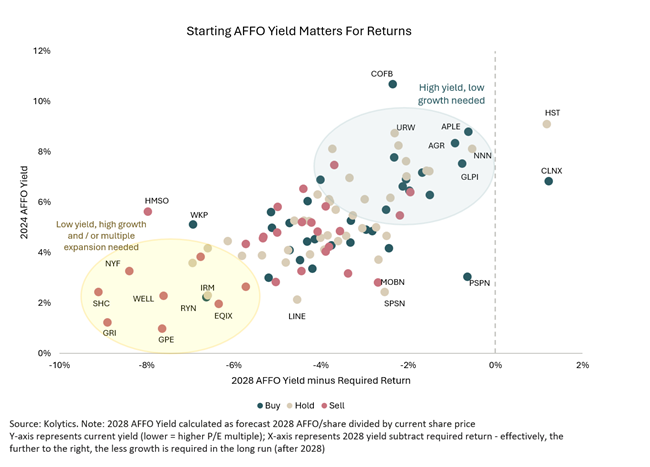

Focusing purely on financial assets, there are three principle components to returns: 1) the current net income yield (after an allowance for additional expenses incurred to sustain the cashflow and assumed growth); 2) current net income growth (often split into short and long-term); 3) multiple change (i.e. the impact of a change in price / earnings multiple on returns). Investors should be somewhat agnostic on which aspect prospective returns come from, but given that 1) is akin to “bird in the hand”, whereas 2) and especially 3) is “bird in the bush”, they should prefer the current income portion of total return more than its growth and multiple change.

When we look at the current market pricing structure in the listed Real Estate Market, it appears low 2024 AFFO yield stocks still have very high growth and / or need multiple expansion (i.e. further yield contraction) from already low levels for 2028 and beyond – in other words, by 2028 the net income is still a small portion of their required returns and this is shown in the bottom left yellow tint bubble. There are companies with high current yields, and by 2028 the low single-digit future growth needed to meet required returns (as shown by the X-axis and top right blue tint bubble) appears more achievable.

The expectations that today’s hot sectors will continue to outperform is nothing new, but the extra valuation ascribed to that growth appears to place a greater level of certainty than seems prudent when considering the historical precedent for disappointment. In the listed sector, many need lofty growth and / or multiple expansion even after 2028 to meet required returns – we are cautious on the bird in the bush, when we can have two in hand.

This article was originally published in The Property Chronicle Spring Issue.