China needs us to buy its stuff more than we need its stuff, but it’s all just noise relative to the stuff that really matters.

I am going to going to offer two somewhat contradictory ideas about trade wars in sequence:

- China needs us to buy their stuff, more than we need to buy their stuff;

- Actually, tariffs don’t matter that much because commerce is like water and it finds a way.

Both of these points will come together in one “actually we’re not so different,” coup de grace.

Now that I’ve told you where I’m going, please join me for the (shortish) journey.

China is losing the trade war, badly

The first point is really a response to the consensus view which is something like “while tariffs will overwhelm the US with spiraling costs and empty shelves, China will just take their business elsewhere, nary an eye blinked.”

I don’t think that’s quite right.

You see, China has become the seller of things to the entire world by design, but it’s not a strategy that originates from a position of strength. It’s a tactical response to an aging (and shrinking) population, whereby domestic demand is in serial decline. For the Chinese economy to grow, therefore, it’s gotta find demand elsewhere—in this case, literally everywhere in the world where people buy things.

If China exports stuff like its economy depends on it, it’s because that’s exactly what it does. Without exports, China stops growing.¹

That being the case, the notion that China could lose access to the biggest consumer market in the world without missing a beat is preposterous. Likewise, the notion that it’d be harder for the US to find substitute stuff than for the Chinese to find a substitute 300 million of the richest people in the world is also preposterous.²

“China will just sell its stuff elsewhere.” Really? To whom?

China is already selling its stuff everywhere. So, where in the couch cushions does China find new willing buyers for billions of dollars worth of microwaves and high-end lighting that Americans now won’t buy? Is there a remote, but numerous and wealthy, Amazonian tribe that’s just a Starlink away from getting the fast fashion bug?

It doesn’t and there isn’t. Obviously.

The point is that China needs the trade war to end, and in the meantime, is experiencing some real economic pain.

Chinese bond defaults have disappeared (lol)

Indeed, China is taking such a beating that Chinese bond defaults have all but disappeared:

After rising in both 2023 and 2024, by 2025 there has been exactly one Chinese corporate bond default in the entire $4T+ on-shore bond market.

Very curious.

Now, one possible explanation for the disappearance of Chinese defaults is robust growth and strength.

The other (more likely) possibility is that the Chinese government is making defaults disappear because, if they didn’t, then everyone would know how much trouble they were in:

Ying Wang, a managing director at Fitch Ratings, said in a written comment that China’s bond market was . . . “predominantly composed of state-owned issuers.” [and] that central and provincial governments had emphasised “minimising public bond defaults among state-owned enterprises to mitigate systemic risk, often prioritising bond repayment over private debt obligations.”

Another analyst, who asked to remain anonymous, said that after a lot of “cleaning up of debt”, the bond market was “now more the domain of the state-owned companies”, and that credit quality had improved “as a consequence of that.” The person added that “implicit government support tends to be highest when the economic picture is more uncertain,” and was currently likely to be “incredibly strong given the economic backdrop.”

S&P data shows only a handful of defaults from state-owned enterprises in recent years, alongside significantly more private-sector defaults.

So, just following the breadcrumbs . . . issuers are increasingly state-owned, and the state tends to lend support when the ‘economic picture is more uncertain,’ and state-owned defaults have disappeared,

I don’t know, could be a coincidence. Data in China is notoriously unreliable, and I’m obviously no expert.

Or, the reason that defaults are disappearing is because the Chinese government is making the distress disappear because, if they didn’t, then there would be a lot more distress.

And there would be a lot more distress because China is taking a beating in the trade war.

Chinese manufacturing is increasingly unprofitable

Here’s another one to file under “actually, China is losing the trade war.”

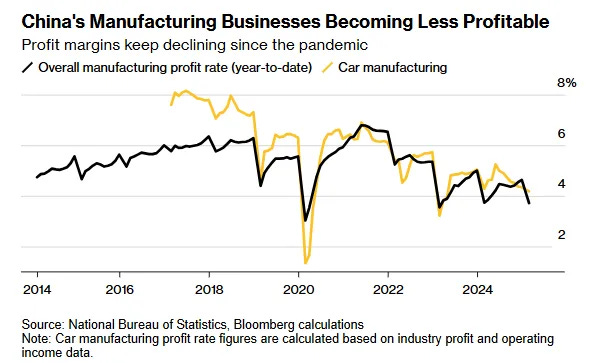

Chinese manufacturing is becoming increasingly less profitable:

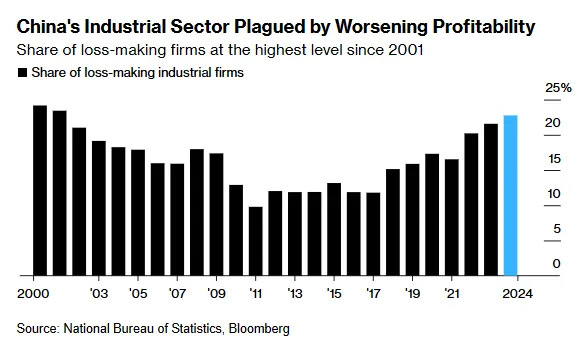

Manufacturing margins have been cut by nearly half from their pandemic peak. Likewise, the share of loss-making companies in China continues to grow:

The share of loss-making industrial firms in China is now ~23%, which is a 20-year high.

Why precisely Chinese manufacturing companies are becoming less profitable, I don’t really know, but I strongly suspect it has to do with aggressively slashing prices to maintain growth and share.

Look, if you were already busily putting German car manufacturers out of business with heavily-subsidised (and impressive) electric cars, and now you’ve got this excess supply of stuff you were planning on selling to the US, but now have to dump on a remote Amazonian tribe, your margins will suffer. There is just no other way.

Tariffs hurt China, more than tariffs hurt the US.³

China is taking a beating in the trade war, because it must—that’s what happens when the biggest customer in the world says, “no thanks.”

Actually, tariffs matter much less than anyone thinks

Now, to be fair, one thing one should obviously notice about both the disappearing bond defaults, and the unprofitability of Chinese manufacturing is that they both appear to be the latest in longer-running trends.

Wait, but you said—

I’m aware, but ignore that for a moment because, while I wasn’t lying, I wasn’t being entirely straight.

Indeed, the pandemic (and not tariffs) appears to have been something of an inflection point. That’s when Chinese bond defaults reversed their upward trend, manufacturing margins began to compress, and the share of unprofitable firms began to rise (although that might have started earlier in ~2018).

That is, rather than some precipitous tariff-driven shift, the evidence is more consistent with a gradual weakening of the Chinese economy. It’s almost like the nation is getting steadily older, and increasingly manifesting the symptoms of a demographic winter.

Sure, to fight back against time, the Chinese government has intervened in various ways, but getting older just stinks, and tariffs ain’t got nothing to do with it.⁴

If that sounds familiar, that’s because it should: hey we’re just getting older, and we’re super-indebted from all our various efforts to defeat time, and finally this structurally weak economy is slowing, and tariffs ain’t got nothing to do with it is a perfectly apt description of the US Economy.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a “worrying slowdown trend” on this side of the Pacific that isn’t at least a year old. We entered the Donna Summers Phase ~April 2024, and it’s been tough-sledding, ever since.

Now, to be clear, tariffs don’t help, and I suspect they are making a bad situation worse (more there in China than here), but mostly they just don’t matter all that much.

Why?

Because commerce is like Bruce Lee, and Bruce Lee is like water, and water routes around and through.

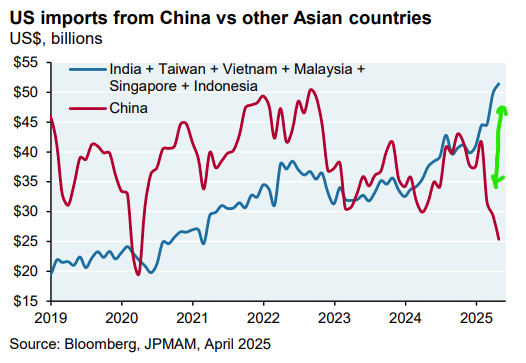

I mean, look what happened to trade flows when Liberation Day came:

~$12B.Now, I’m sure some of this is genuine supply-chain resilience, but (a) we already knew that every third business in Vietnam is a Chinese business; and (b) obviously a lot of this is just customs chicanery.Did Mexico get good at making washing machines or did Chinese manufacturers just set up shop in Mexico? The reality is that generalised tariffs are just really hard to enforce.⁵ They either have to be total—and, well, those are pretty costly—or, as Alex Kolicich argued, sector-specific where the provenance of a narrow subset of goods can actually be interrogated (maybe).Otherwise, tariffs just don’t matter all that much.

- Is it probably correct that China is more vulnerable in the trade war? Yes.

- Is there data to support rising economic pain in China? Also yes.

- Is the trade war a prime mover in that economic malaise? Not very likely, no.

As with the US, there are bigger, structural issues afoot in China (and we’ve got a lot more in common, than we’d like to think). The trade war matters like throwing rocks in a stream—it’s not nothing, but pay too close attention, and you’d be losing the forest for the trees.⁶

References

1. This seems about right: if we use deficits to finance consumption to grow our economy, then China uses deficits to fund production to grow its economy.

2. That is unsurprisingly why the sticking point has been around batteries and the rare earths that are required to make them, because those actually are hard to substitute.

3. Where the US is vulnerable is our insatiable demand for borrowing. As I’ve quipped previously,

The catch, of course, is that while China depends on the world to buy its stuff, we depend on the world to buy our debt. We raise a lot of debt, and if other countries say “hell no,” well, that’s their leverage—if you thought rates were high before, just wait until China, Japan and the UK start dumping treasuries

We can live without China’s stuff. We can’t live without the world’s lending. The thing is that it’s not like all our lenders can suddenly devalue their UST either bc, y’know, that would be seppuku.

4. More precisely, as I’ve observed for a while, China appears to be preparing for its demographic winter differently. It’s been stocking up on real stuff (rare earths, gold, pork, energy, etc.) and robots. We, on the other hand, just borrow a lot to spend on healthcare.

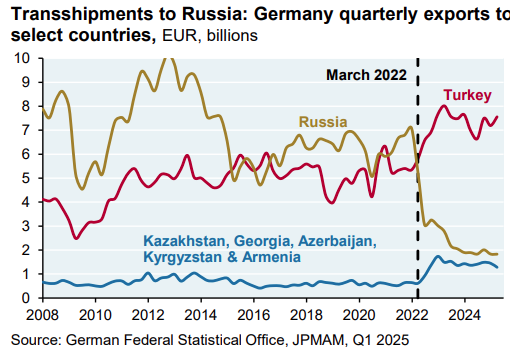

5. Remember those Germans? Well, while they were busily being outsold by China, they decided to make money by selling lots of stuff to Russia instead, the country they are supposedly at war with, with just a little sleight of hand.

Germany erased ~50% of its decline in Russia exports by routing through Turkey instead. This is almost as egregious as buying tons of Russian oil by calling it Indian oil. What a joke.

6. To mix nature metaphors, because it’s my newsletter and I do what I want.

This article was originally published by Random Walk.