Dogs have become a plague on urban life. Don’t get me wrong, I love dogs. Growing up in rural Arkansas in the 1980s and 90s, our family regularly adopted abandoned hunting dogs. At one point we had over a dozen dogs.

Dogs can be wonderful.But in American cities today, dogs are completely, entirely out of control. From dogs running around grocery stores to “ESAs” sitting in restaurants to toddler proxies wheeled around in strollers, dogs are transforming our built world and society in deep and uncomfortable ways. Today’s Thesis Driven rant letter is on dogs and their growing impact on cities, families, and urban life.

The Numbers

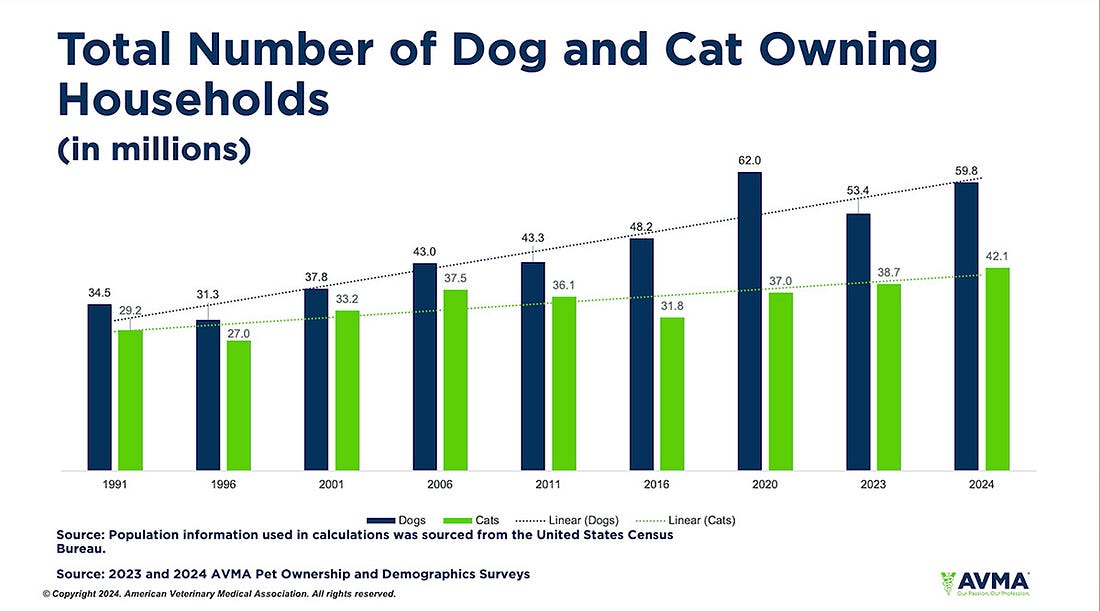

It’s impossible to talk about dogs in America without acknowledging a simple fact: there are way more of them than there have ever been. Dog ownership exploded in the US over the past ten years, growing from 48.2 million dog-owning households in 2016 to almost 60 million in 2024. And an outsized share of those new dogs were pit bulls, America’s most popular dog breed. (We’ll put a pin in that for now.)

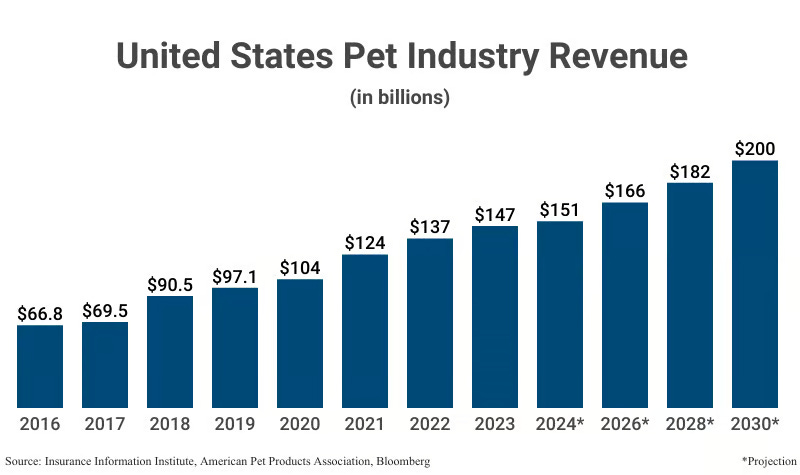

Simultaneously, pets—particularly dogs—have also become a major expense item for American households, with spending on pets more than doubling over the past decade. Pet insurance, often running $500 or more per year, has become yet another line item in the menagerie of insurance products Americans are expected to buy.

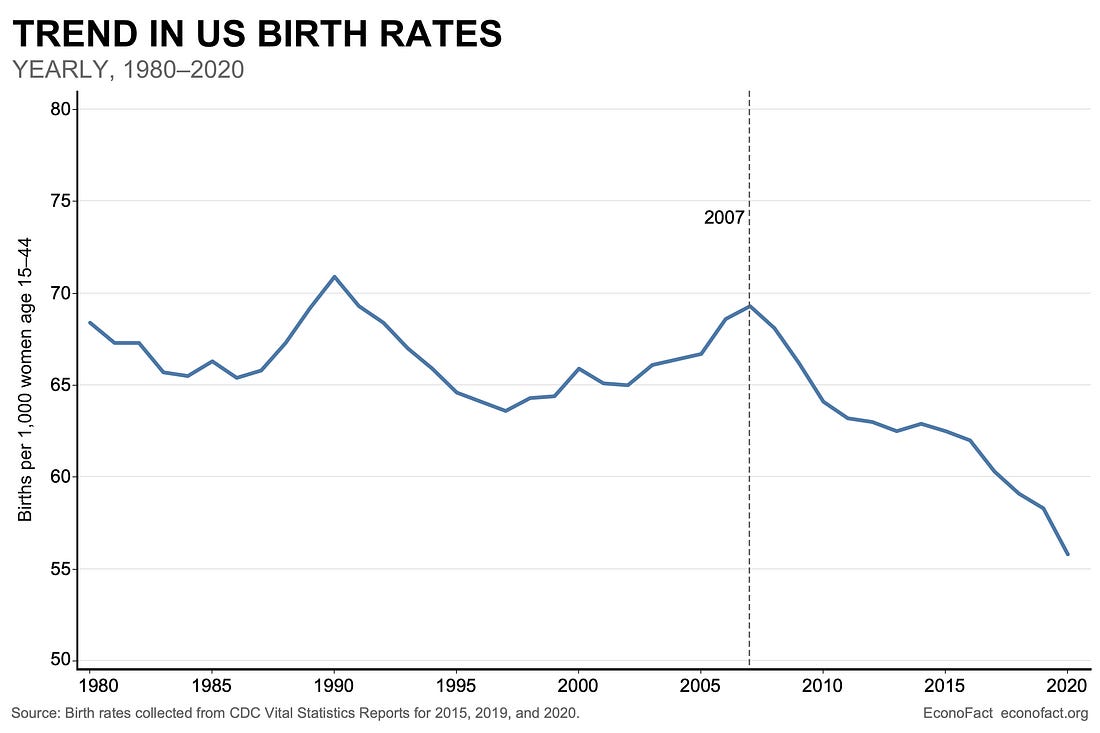

While the population of dogs has exploded, the number of children has cratered. The timing of these trends is eerily aligned, with the most recent drop in fertility (down to well below replacement levels) lining up neatly with the growth of dog ownership—increasing over the past 20 years and accelerating post-2016.

It’s not hard to reach the conclusion that dogs are replacing children in many Americans’ lives, especially when dogs increasingly outnumber kids in major US cities—cities that are building new dog parks as fast as they shutter schools and playgrounds for lack of demand.Apartment industry insiders have observed a similar trend. Dog spas, pet concierges, and “dog runs”—patches of fake grass where dogs can poop—are consistently near the top of lists of “must-have” apartment amenities. Playrooms and playground equipment, on the other hand, are almost never

Dogs and people

While the proliferation of urban dogs might be bad for cities, some argue, they’re invariably good for the people who own them.

But the personal experiences of my own friends and colleagues suggest otherwise.Here’s a scenario I see play out time and time again:

There is a young couple living in a major US city. Late 20s to early-to-mid 30s. They’re in a committed relationship – perhaps married, perhaps not – but not quite ready to make the leap to having kids. They want to get a bit further in their careers, make a little bit more money, maybe upgrade to a two-bedroom apartment.

So they decide to get a dog instead.

In the months after taking their new puppy home from the breeder, work gets busy, and the training regime they planned to enforce loses steam. Confined to a small apartment, the dog develops mild anxiety, barking at footsteps in the hallway and jumping on visitors whenever they arrive. The couple is eventually forced to lock the dog in the bedroom whenever guests come over.

A few years pass, and the couple—now solidly into their mid 30s—decides to finally make the leap and have a kid.

The new baby dramatically changes the couple’s relationship with their dog. Previously a mild annoyance, the work of taking care of the dog—now that the allure of the puppy has long worn off—becomes a burden on top of the responsibilities that come with a newborn. Being woken up by Rufus at 5am was frustrating before; when combined with the baby’s nursing schedule it’s infuriating.

Now the couple resents the dog. They wish they had never gotten it. The late-night walks are a burden. The vet bills are an imposition. They don’t talk about the dog any longer—neither with family nor with friends. Baby videos take the place of dog photos on their walls and in their minds.

Months pass. In a best-case scenario, the dog merely ignores the baby. But after living in a small, confined apartment for several years, the animal has developed serious anxiety and now growls at the toddling child whenever she gets too close to the food bowl. The couple is tense, but they reassure themselves. “She grew up with the dog. They’re family.

”One day, the dog nips at the toddler. The bite mark is small—and there’s not a lot of blood—but it’s undeniable.

Reality sets in. There are tears. The couple confers with close family in hushed tones. They don’t acknowledge what happened to friends—this isn’t a thing to be discussed casually.

The next day, Rufus is gone. There are a million variations to this story, but they all have similar dynamics and tensions. Perhaps Rufus never bites the toddler. The couple’s resentment and frustration builds, but there is never a spark that prompts them to give up the dog. So the dog gets older, growling every time anyone approaches its food bowl—and weighing on the couple’s time and budget. Vet bills pile up. Exhausted, they decide against having a second child. Rufus eventually passes away when the little girl is eight. The couple is relieved; the little girl cries, unknowingly burying the thing that denied her a little brother or sister.

Society

Dogs have a place, no doubt. For older Americans, pets stave off loneliness and isolation. In suburban and rural environments with plentiful outdoor space, dogs avoid anxiety and get exercise without constant walks. And taking care of a well-trained dog can help older children develop a sense of responsibility. Private outdoor space also means dogs don’t crowd public outdoor spaces—there’s no externality when your dog poops in your own yard.But we are increasingly redesigning cities around the needs of dogs and their owners. Off-leash dog parks are the fastest growing type of urban public park in the US, and there are now almost a thousand dog parks across our country’s hundred largest cities. And as they spend hundreds of millions of dollars on dog parks, cities are tightening the leash on daycares, giving in to pressure from NIMBYs who see children as nuisances. (This episode of NIMBYs protesting a new playground in LA is a great example.)

Widespread misuse of ‘Emotional Support Animals’ (ESAs), often wrongly associated with the Americans with Disabilities Act, has further emboldened many dog owners to claim space for themselves and their animals. While there are no official statistics on the number of ESAs, The National Service Animal Registry—a for-profit company selling paraphernalia like vests and fake certificates to ESA owners—claims to have served more than 200,000 animals. The actual number of ESAs, the vast majority of them dogs, is likely far higher.

The “ESA” label is powerful, giving owners permission to bring untrained dogs to places where they are generally prohibited like restaurants and grocery stores. On a typical afternoon trip to my local Manhattan Whole Foods, I’ll probably come across four to six dogs per visit despite a sign on the entry door clearly prohibiting them. As I was checking out last week, an emotional support Labradoodle was rustling through my bags. (Notably, many people with actual disabilities who require licensed service animals hate ESAs, as they are often confused with actual service animals and occasionally attack them.)

No one of these societal impositions are terrible on its own. But taken together, they represent a seismic shift away from a society that supports children and families to one that supports dogs and dog owners.

But with a total fertility rate of 1.6 and dropping, we need to be headed in the opposite direction, encouraging kids and making life easier for parents. Otherwise, we’ll face the kind of demographic disaster currently looming over many Asian and Eastern European countries where increasingly few young people are supporting an ever-larger pool of retirees.

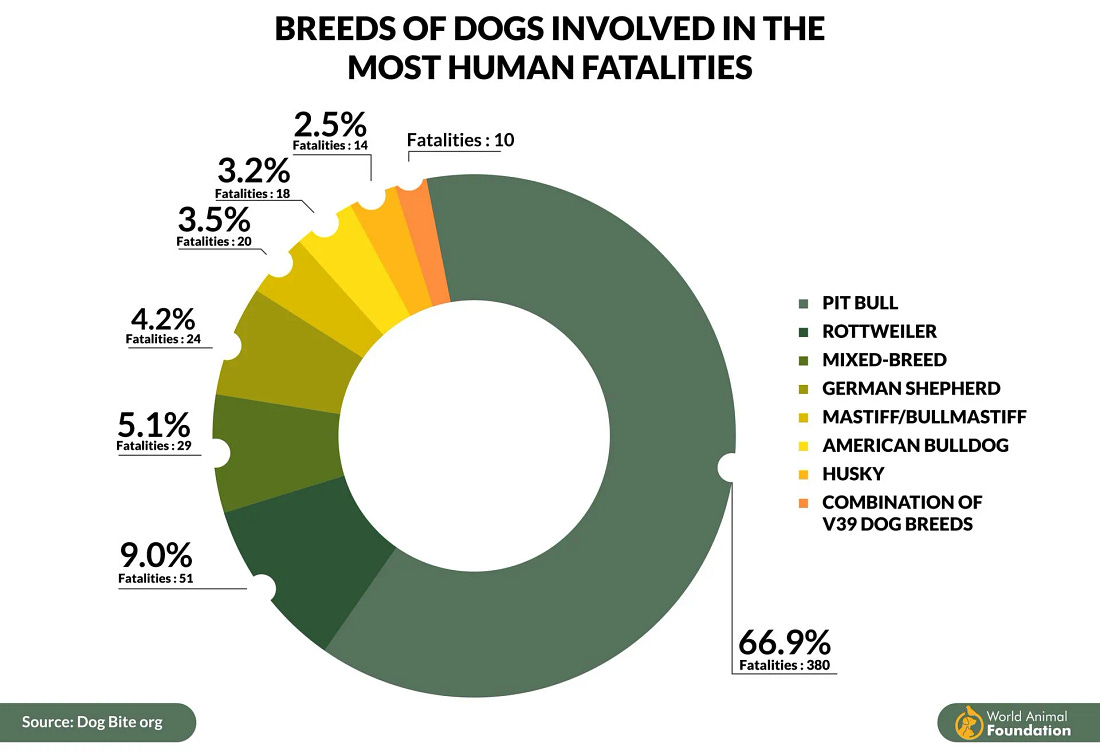

There is no better metaphor for the role of dogs in modern American society than the explosion of pit bull ownership. Despite making up only 6% of the US dog population, pit bulls represent 66% of all fatal dog bites, six times as much as the second most dangerous breed. Children between the ages of one and four are the most common victims, and many of the victims were killed by their own family dog. “She was always such a perfect angel,” the owner tells local news when asked about the family pit bull.

Predictably, the rise in pit bull ownership has corresponded to a dramatic rise in fatal dog attacks. There were 81 fatal dog attacks in the United States in 2021, a 131% increase from 2018—the majority involving pit bulls.

Unfortunately, cities are passing laws that make it harder for building owners to create safe environments for families. DC’s Roscoe’s Law—named after a legislator’s rescue pit bull—prohibits building owners from putting restrictions on dog breed, weight, or size. So if a new neighbour moves into the unit next door with three 60 pound pit bulls straight from the shelter, the DC government insists that they share an elevator with your kids.

All of this is a choice. As a society, we choose the results we want by the behaviours we allow and the environment we built. And right now, the results we want are childless cities filled with dogs.

This article was originally published by Thesis Driven.