What’s gold today may be coal tomorrow.

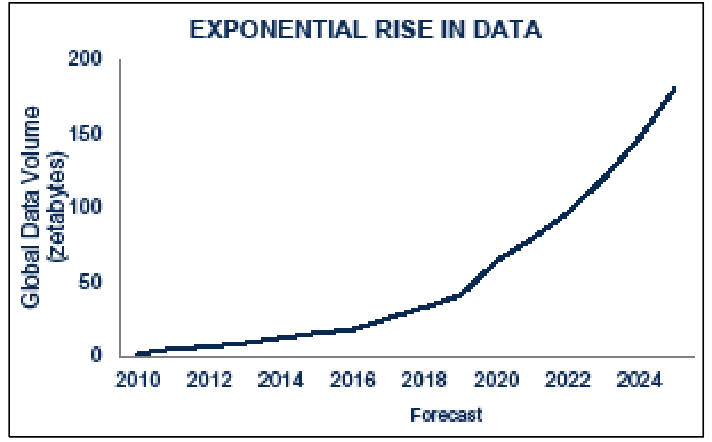

It has been 15 years since Apple catapulted the smartphone into the mainstream, with the launch of the iPhone 1. Today there are more than six billion (and rising) smartphone users globally, all with a plethora of data services and demands. Mobile data is just the tip of the tech and data iceberg, if you think of just the digital devices in your own home, place of work and those under development (eg, AI, automated vehicles, climate technology, etc). As the digital economy continues to expand, so too will the necessary supporting digital infrastructure and data storage capacity, pushing data centre demand on an exponential trajectory.

Their appeal

In addition to a phenomenal growth story, data centres have other compelling investment attributes, typically offering longer lease terms than other property types and index-linked rents – extra attractive in the current inflationary climate. While robust performance data is still lacking, intuitively, data centres are likely a-cyclical and strong diversifiers, reflecting that data demand is likely, less directly connected to economic and property cycles than the conventional property types. An allocation to a diversified portfolio should therefore provide added downside protection in property market downswings.

With data centre prime yields at around 4%, the spread to other prime European mainstream real estate has now effectively closed and with it ‘first mover’ advantage. There are also US REITS specialising in the sector (eg, Digital Realty [NYSE:DLR] and Equinix [NASDAQ:EQIX)] which both own and operate hundreds of centres across the world). That all seems to suggest that the sector has now fully matured and is an established property type.

Too good to be true?

Yet it remains a highly specialised asset type. Data centres’ high power requirements mean that they’re a world apart from standard industrial units. Not all locations will be suitable due to local power grid constraints. Where capacity does exist, initial costs to install the necessary power supply infrastructure will be high, as will the cost of any required future power upgrades. This is also an example of what gives a data centre a locational characteristic, moving it away from a network infrastructure asset to become a real estate investment in its nature.

Ambitious EU targets to make data centres carbon neutral by 2030 will increase sector pressure to boost energy efficiencies and reduce dependency on non-renewable energy sources. Expect to see increased scrutiny of individual facilities’ non-renewable energy consumption and energy waste. While new facilities can incorporate measures to optimise energy efficiencies into the design process, existing centres could potentially face high levels of CapEx to meet stringent energy targets.

Paradoxically, the greatest risk to the data-centre market is actually technology itself. Because future technological innovation is unknowable, todays state-of-the-art asset and perfect location could potentially become functionally obsolete tomorrow. For example, the low latency/proximity required for automated vehicle development could be negatively impacted by a step change disruptor, eg, 5G satellites/Starlink, etc. Does that mean the zero spread to all-property yields isn’t a sign of maturity, but just the disappearance of an allowance for future extra CapEx and obsolescence risks?

Time your exit strategy

Data centres certainly have highly attractive investor attributes, given the sector’s exponential growth prospects and their ability to provide long index-linked cash flows and even the prospect of powerful diversification potential. That should point towards a large core property portfolio allocation, held for the long term. Although, given the rapid pace of technical innovation, that is what more likely guides a core investor’s investment horizon. Perhaps the lower risk option is to be involved in construction debt funding or take pre-commitments and execute on a value-add business plan basis.