In 1920, an Italian immigrant in the US called Charles Ponzi claimed he could buy International Reply Coupons (IRCs were essentially prepaid stamps) cheaply in Europe, where currencies were weaker, and redeem them in the US for more valuable U.S. postage — then profit from the exchange difference or arbitrage. He promised investors 50% profit in 45 days or 100% in 90 days.

“The scheme relies on a continuous flow of new capital to survive — once that flow stops, it collapses.”

What actually happened was Ponzi never bought enough IRCs to support the returns he promised. The postage scheme was technically possible, but on a very small scale. Instead, he simply used money from new investors to pay earlier investors — classic Ponzi scheme. Bernie Madoff serves as another example, being modern, long-term (17 years), and the largest in history.

A Ponzi scheme is a fraudulent investment scam that promises high returns with little or no risk, but instead of generating actual profits, it pays earlier investors using money from new investors. The scheme relies on a continuous flow of new capital to survive — once that flow stops, it collapses.

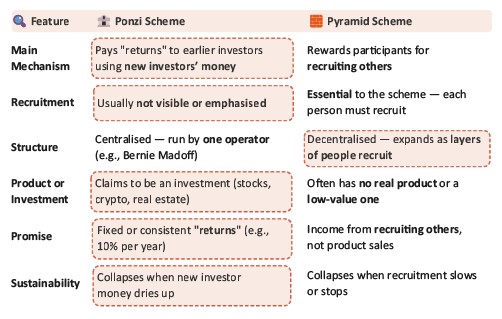

The scary and uncanny resemblance to the stock market is all too evident on closer inspection and this has been highlighted by the dashed red lines in the table. Let’s take these features in turn and flesh out the context that applies to today’s market.

Main Mechanism: New investors coming with incremental capital (pension funds, trend following algorithms, ETFs, retail investor speculation via levered ETFs and one day expiry options, etc…) and financial innovation over decades have bid up prices. These higher prices create “wealth” which can be margined/levered up to bid up prices further and in doing so valuation multiples have risen faster than corporate profits. The multiple expansion is a one-time benefit but can also drag returns when multiples return to historical norms or below (as they typically do).

Recruitment: The current cycle is not unique; this has happened across many market cycles; investors pile in at various points of the next new hype or fad and those making big gains are the best walking / talking advertisements on social media and other forums. The temptation to join in grows and grows, but with strong multi-year performance the benefits have not been shared equally, and certain sectors and stocks have taken the lion’s share.

Structure: Financial innovation and accessibility of levered ETFs and Zero-days-to-expiration options coupled with growing use of margin accounts have facilitated high retail participation in the stock market once again. Falling trading costs and historically low interest rates have also added to the appeal of the stock market to the masses.

Investment and [implicit] promise: The lower perceived risk of stocks, as measured by falling implied option volatility and the strong sustained returns since the GFC, means that the current crop of investors believe the stock market is relatively low risk compared to those who lived through previous correction phases. The most recent bailouts of the stock markets (during GFC) and economy (during Covid) have conditioned investors to a FED and Government PUT that is more than the minimum necessary to restore ordinary functioning of markets. These protective PUTs may have helped ordinary people in the near-term, but the long-term effects have been to inflate financial asset bubbles and help bail out the rich who own most of these assets.

Sustainability: The issues raised above are not just limited to the stock market, but the economy and government deficits too. All these areas feed on each other and drive excesses to a point where they are not sustainable and require new participants in ever larger numbers.

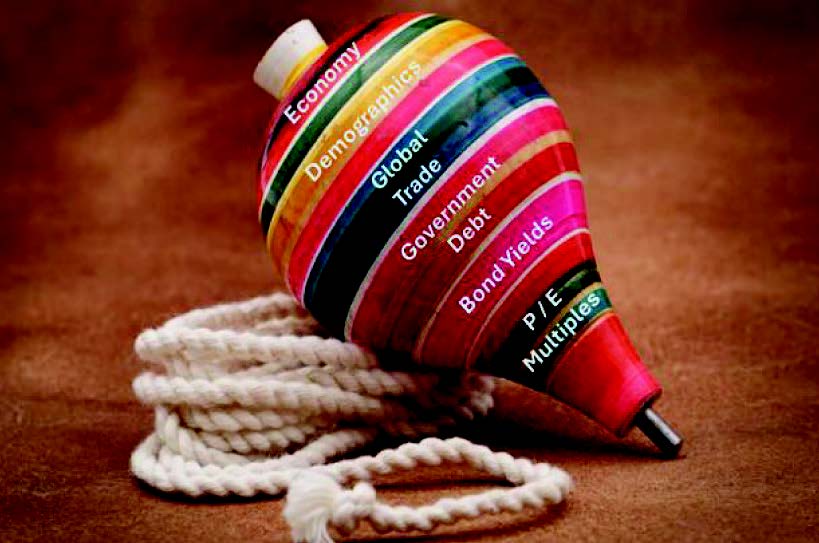

The trends that drove steeper valuations in a bygone era – i.e. 1) low starting debt and falling yields; 2) low valuations; 3) increasing globalisation; and 4) strong population growth – are now fizzling out or going in reverse. The Make America Great Again (MAGA) approach is bizarre given that “American Exceptionalism” already pointed to both absolute and relative greatness, but the effects of MAGA policies and trade wars run the risk of rebalancing capital away from an overweight position to American assets – that’s less new money not more.

“The era of globalisation and positive demographic trends is over for most developed and large economies.”

All hands on the pump

Most publicly listed companies have good prospects, but companies end up losing a competitive edge or the industry goes into decline and therefore the returns might be negative or sub-par, but often still nominally positive. Some small fraction of companies perform strongly for generations.

Most institutional investors have a good sense that big, technology-led companies with a good moat have very high valuations. They know that these high-quality companies will need to deliver market-beating growth for many years to come and that the likelihood of doing so in an economic downturn is low. There are plenty of imbalances that have built up over decades and this cannot continue. The era of globalisation and positive demographic trends is over for most developed and large economies. So, the angular momentum needed to keep the local and world economy spinning uninterrupted is losing steam.

So why do active fund managers and institutional investors stay invested at lofty prices? Simply because they get paid to and if they don’t do it their employer will find someone else to take their place. For those few that have the latitude to go it alone but then get it wrong, they will be gone in no time – surprisingly more so in bull runs than bear turns – there is, therefore, something to be said for the safety of crowds.

As long as there is marginal new money, valuations can be kept high. As long as large deficits loom, GDP will be artificially inflated. As long as governments can borrow from unprotesting yet-to-be-born generations, they will. The promise of FED and government backstops are powerful mechanisms that keep pumping the stock market scheme…one of such scale and longevity that even Charles Ponzi would be proud of!

This article was originally published in the Summer Issue of The Property Chronicle.