When the UK voted to leave the European Union on June 23 2016, many people could not understand how David Cameron could have allowed such an important decision to be made by, of all people, the voters.

Some saw the decision to call a referendum as an unnecessary move — especially on the pro-EU establishment side of the debate.

There is one country in Europe though where Britain’s decision to hold a referendum on its membership of the European Union was not only seen as understandable, but probably, in the fullness of time, as unavoidable.

I’m referring to the country of direct democracy and referendums : Switzerland.

A landlocked group of 26 proud cantons surrounded by the EU where citizens defiantly maintain a strong influence on their political class by holding regular referendums on a whole host of political issues. So deeply engrained in the national psyche is the idea of voters having a say that even relatively unimportant political decisions on issues such as VAT or TV licence fees are taken by plebiscite.

While the democratic tradition is also famously well established in Britain, the idea of holding national or regional plebiscites is less so. However, Britain has moved closer to Switzerland in recent years and embraced a more direct form of democracy when it comes to important constitutional questions. Referendums on North East England devolution (2004), Welsh devolution (2011), the UK parliamentary voting system (2011) and Scottish independence (2014) were all held just a few years before Britain’s referendum on EU membership.

It may be unavailing to speculate now, but had the British people been given an earlier say on their membership of the EU – for example when the Maastricht, Constitutional or Lisbon treaties were passed by UK MPs without referendums – we might not have found ourselves in the difficult position we do today.

The Swiss political analyst Dieter Freiburghaus said something that will have resonated with many British voters when he was interviewed by the BBC before the Brexit referendum:

“Switzerland was only interested in the economic aspect of European integration, and that we got: we got access to the internal market. So our economy had a lot of gains. We have the cake and we eat it… at the moment.”

Today’s European Union is politically integrated well beyond the Common Market that the British electorate signed up to after the 1975 European Communities (EC) referendum. In fact, it has since then integrated politically well beyond what most would have agreed to, had their opinions ever been sought. Britain was always primarily interested in the commercial benefits of EU membership, rather than the political. In that sense, Swiss expectations from their relationship with the EU are very similar to British voters.

So, as Britain pushes on this week with negotiating a particularly British model of cooperation with the EU – having categorically stated that it won’t seek membership of either the Single Market or the Customs Union – the Swiss model has once again risen to the fore and warrants some renewed attention.

To really understand the Swiss model, it is worth turning the clocks back to 1992. It was precisely as the British Conservative Party was tearing itself apart over the controversial implementation of the Maastricht Treaty that Switzerland held its most important EU referendum. On 6th December 1992, the Swiss narrowly rejected European Economic Area (EEA) membership in the last of 15 (15!) referendums it held that year.

By rejecting the EEA model, Switzerland was now destined to develop its relationship with the EU in an ad hoc, incremental manner. Greater cooperation may have been desired by both sides, but it was clear that the Swiss were more attached to their sovereignty than had been expected. The incremental model was also very appealing to officials who had found a new respect for the Swiss electorate after the shock 1992 referendum.

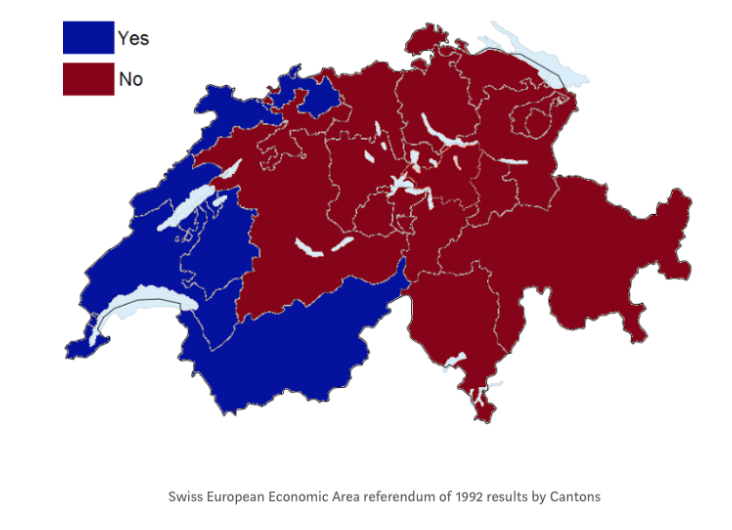

That referendum was as divisive for Switzerland as the 2016 referendum has been for Britain. The pro-EEA campaign managed to lose what was at one point more than a 50 per cent lead in the polls –the country finally voting 50.3 per cent to 49.7 per cent against the proposal.

The vote split the country along “national” lines, just as the Brexit referendum would, 14 years later. French-speaking cantons backed deeper EU integration while the German and Italian-speaking parts of the country rejected it.

The vote also revealed another divide within the country that mirrored the Brexit result and also heralded the later manifestation of the anti-elite sentiment so prevalent in our politics today. By rejecting stronger ties with the EU, Swiss voters, particularly in more rural communities, ignored the recommendations of political, intellectual, industrial, business, banking and labour leaders.

It is this key rejection of deeper integration with the EU that laid the foundations for the “living agreement” that Switzerland currently enjoys with the EU – a series of treaties developed incrementally in response to specific circumstances rather than being an off-the-shelf framework for cooperation like the EEA agreement.

Based on a number of comprehensive bilateral deals that cover the four freedoms of the EU as well as numerous sectorial agreements, the Swiss model currently comprises over 120 bilateral agreements designed to secure Swiss access to the EU market, and vice-versa. It is a relationship also secured by Switzerland’s participation in the European Free Trade Area (Efta), and it rejecting membership of the EU’s Customs Union.

This patchwork of agreements makes the Swiss model the most complex. Yet despite this complication, and despite the fact that over 55 per cent of Swiss exports go to the EU (compared with around 45 per cent of the UK’s), Switzerland has never reversed its 1992 referendum result on EEA membership.

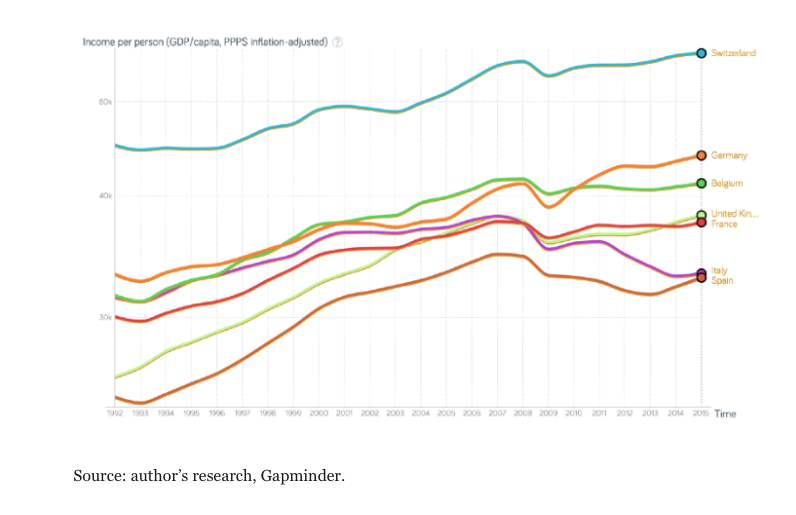

As the graph below also shows, Switzerland continues to be one of the world’s best performing economies. It did not fall into years of recession as some threatened it would during the 1992 referendum campaign. When it chose to reject the EEA in preference for an independent trade policy and a freer hand in making its laws, the Swiss economy continued to perform strongly. In fact, since the 1992 referendum, the Swiss economy has regularly been labelled the world’s most competitive and many of the world’s most successful companies – such as Novartis, Nestle and Glencore – continue to thrive in Switzerland under its bilateral agreements with the EU and the trade deals it has signed with non-EU countries.

It is also notable to point out that the Swiss government has never re-applied for outright membership of the EU. In fact, the opposite is true. One week before Britain’s EU referendum, Swiss MPs voted to officially withdraw the country’s application to join the EU – an application that had lain dormant since the 1992 referendum.

However, while the Swiss may have lost interest in deep political integration with the EU, that is not to say that they are happy with the level of commercial access their current bilateral relationship with the EU grants them.

The Swiss economy’s strong focus on banking and financial services mirrors closely that of the UK, but given that cross-border cooperation in these areas remains underdeveloped in the EU, the Single Market benefits in these sectors remains unsatisfactory for economies weighted towards services.

The Swiss Council – the country’s federal parliament – prioritises “broad and secure access to the Single Market, and a clearer legal status” but the Swiss government is disapproving of the current agreement where “existing barriers to market access place Switzerland at an economic disadvantages”.

While existing sectoral deals in goods have proved highly advantageous to both sides, and Switzerland’s ability to sign free-trade deals with whomever it chooses appeals greatly to the more global-minded “leave” supporters, it is clear that the UK, like Switzerland, would find an EU agreement that does not sufficiently incorporate services as inadequate.

As Switzerland sought to address this and improve its access to the EU market, it initially sought to sign new agreements with Brussels in the banking and financial services sectors. However, the EU had by then firmly lost patience with the ad hoc, Swiss model of negotiating and signing agreements.

In December 2012, the EU Council stated in its conclusions on EU relations with Efta countries that: “[…] the approach taken by Switzerland to participate in EU policies and programmes through sectoral agreements in more and more areas in the absence of any horizontal institutional framework, has reached its limits and needs to be reconsidered. Any further development of the complex system of agreements would put at stake the homogeneity of the Internal Market.”

A House of Commons report released after the Foreign Affairs Committee visited the Swiss capital in 2012 also found that the likelihood of the EU entertaining a Swiss type deal for the UK was highly unlikely: “Since December 2010 the EU has been refusing to move forward on any further bilateral agreements that Switzerland might seek until the Swiss Government agrees to establish an overarching institutional framework that would ensure the homogenous interpretation and application between the EU and Switzerland of the relevant Single Market rules.”

But what is it in particular that the EU has come to so dislike about the Swiss model, and which it is therefore highly unlikely to offer to the UK in Brexit negotiations?

Well, in the first instance, the sheer complexity of the bilateral deals has lead to institutional deadlock in a number of areas. Furthermore, the EU is concerned that the addition of new agreements would escalate complexity to an unsustainable level, threatening the homogeneity of the Single Market, increasing legal insecurity and potentially undermining EU relations with third parties.

The EU is particularly concerned by the lack of a suitable legal framework that is applicable to all existing and future agreements and that would ensure the consistent interpretation and application of Single Market rules. It is also troubled by the lack of a mechanisms for monitoring and judicial control, although, as has been suggested for the UK, a compromise does appears to be forming around the idea of arbitration panels to resolve such disputes.

Another serious concern is the weak legal footing on which the entire Swiss-EU relationship rests. Switzerland’s strong democratic tradition threatens its bilateral agreements with the EU (as well as its other international agreements, for that matter) because of the possibility that it may unilaterally contravene clauses previously agreed to. This is particularly dangerous because EU-Swiss bilateral treaties on Single Market participation include “guillotine clauses” that threaten to terminate all agreements if just one is discontinued.

The controversial 2014 immigration referendum that actually instructed the Swiss government to impose quotas on EU immigration is a perfect example of just how unstable the existing agreements can be.

Brussels was shocked by the referendum result and made it very clear that freedom of movement was not up for negotiation. It initially froze electricity supply talks with Switzerland. Then, in response to Bern refusing to open labour market access to Croatia shortly after the referendum, Brussels downgraded Switzerland’s membership of the Horizon2020 scientific research programme and suspended its involvement in the Erasmus student exchange programme.

Such fragility surrounding the Swiss-EU agreements has long been a serious concern for both sides and as such, a concerted effort has been underway for over a decade now to find a way out of this impasse.

Both sides agree that a new overarching accord is needed that addresses the main concerns highlighted above: namely the complexity stemming from the plethora of existing deals; the fragile foundations they are built upon, given Switzerland’s direct democratic tradition and the guillotine clauses, and the lack of an adequate legal framework for resolving disputes.

Had Switzerland unilaterally cancelled “free movement” agreements after its 2014 referendum, its access to the Single Market would have been under threat, putting thousands of jobs at risk. In fact, even before the 2014 referendum, Switzerland had already angered Brussels when it re-introduced quotas for certain categories of residence permits for citizens from 8 EU Member States.

Ultimately, three years of internal squabbles saw the Swiss federal parliament approve legislation in 2016 which dropped the contentious quotas on EU immigrants in favour of a national priority hiring system – although this was strictly limited to regions and sectors with high unemployment. This compromise was welcomed by the EU, and in April 2017, discussions on the framework accord were reopened.

This new Swiss-EU deal – the Institutional Framework Agreement (IFA) – seeks to reassure politicians, officials, businesses, investors and voters that the entire bilateral relationship can’t be brought down by a disagreement or a referendum on a single contentious issue.

This concern is highly relevant to Britain’s future relationship with the EU too. The British establishment may have somewhat lost its appetite for referendums for the time being, but the country could easily find itself holding a referendum in the near future on a whole host of issues, such as EU freedom of movement, PESCO defence cooperation or Common Fisheries Policy quotas.

Were the UK deal to mirror the Swiss deal, Brussels and London would have to go straight to some British variant of the IFA, rather than seeking to put in place anything like the 120 bilateral agreements of the current Swiss model.

Whatever model of cooperation the EU, Switzerland and UK ultimately settle on, it’s clear ministers and officials on all sides have their work cut out.

The British people’s decision to leave the EU placed highly mediatised and almost insufferable pressure on the British government. It has also put significant pressure on the EU though. The euro, migration and democratic crises in Europe that contributed significantly to Brexit are yet to be satisfactorily resolved. The EU is weak and having to hold simultaneous negotiations with the UK and Switzerland at this time is far from ideal from Brussels’ point of view.

The EU had hoped to complete negotiations on the IFA before the disruption of Swiss and EU elections to be held in 2019. It also hoped to have the accord finalised before negotiations on Britain’s future relationship with the EU really began. That deadline looks increasingly difficult to hold to.

The Remain campaign in Britain regularly argued in the run-up to the referendum that bigger countries secure more favourable agreements than smaller ones – given the larger markets they bring to the negotiation table. By that logic, the UK-EU deal should prove to be more appealing to Bern than anything it could negotiate with the EU.

The EU is determined to avoid any such coordination of interests between Switzerland and the UK though, for obvious tactical reasons. EU President Jean-Claude Juncker was clear about this when he stressed the importance of: “not mixing up the negotiations with Great Britain and the negotiations with Switzerland. These are two completely different procedures.”

However, in practice, this is proving harder to enforce. With the process of Britain tearing itself away from the EU under a strict timetable and the Swiss negotiations under no such pressure, Bern can just wait out the Brexit process. This would allow it to take full stock of those negotiations and to then potentially cherry-pick the most appealing aspects of any final EU-UK deal.

This is not a scenario Brussels wants to entertain. They have repeatedly made calls for the institutional framework accord to be finalised as soon as possible. In April 2017, EU President Juncker hopefully stated: “We will work intensively to complete the framework agreement before year’s end and solve all the controversial questions.” That deadline quickly passed without enough progress being made.

The EU did then try to exert pressure on Switzerland to speed up negotiations. It controversially placed the country on its tax evasion “grey list” in December 2017 in a move that was widely interpreted as a response to the slow progress in Bern towards a new accord.

Another move that was also inextricably linked to the delay in negotiations was the decision to restrict Swiss stock exchange access to the EU market to just one year. The EU made it clear when that announcement was made that no further market access could be granted to Switzerland until the new institutional agreement was in place. Britain was, revealingly, the only country to vote against that decision.

The tough stance adopted by Brussels appears to have backfired though. The Swiss Federal Parliament is dominated by the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP) which is by far the most eurosceptic party in Switzerland. They regularly form a significant part of Switzerland’s coalition government and they didn’t take kindly to Brussels’ bullying tone.

Quick to pour cold water on a new Spring 2018 deadline unilaterally proposed by Jean-Claude Juncker, Swiss Finance Minister Ueli Maurer – a leading member of SVP – stated that a deal before Brexit in 2019 was unlikely. Arguing that it wasn’t in the Swiss mentality to move so quickly, he said: “If we try it nonetheless, both sides will be under pressure and this will not lead to good negotiating results.”

Later that month, Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis, this time from the Swiss Liberal Party, also dampened hopes of a quick resolution. He argued that quality was more important than timing and that Switzerland would not settle for just any framework agreement but one that takes Switzerland’s interest into account.

The difficulty for Brussels to keep two simultaneous negotiations separate is now conspicuous. As Swiss newspaper Le Temps explained, the difficulty for Brussels also lies in it giving in too easily to Swiss demands while London looks on: “What Switzerland can obtain today from the EU, Britain will be tempted to ask tomorrow. This is increasingly disturbing for Brussels.” Gerhard Pfister, the leader of the Switzerland’s Christian Democratic Party, also commented on the difficulty of holding parallel negotiations: “[The EU] currently has an open flank with Great Britain. Issues such as stock market equivalence will play a role in future relations with the UK. The EU does not want to make concessions to Switzerland faster than the UK.”

So, the EU clearly wants to avoid establishing an official link between Brexit and Switzerland, however, as the Neue Zürcher Zeitung newspaper reported, in reality it is almost impossible to separate the two: “In a confidential conversation, however, EU officials admitted that when deciding on bilateral dossiers, the consequences for negotiations with London must always be taken into account.”

The Swiss model of cooperation with the EU is far from perfect. These flaws can hardly be downplayed too when both Bern and Brussels are actively working towards a new IFA that seeks to fundamentally reform their relationship. That fact alone seriously limits the appeal of the Swiss model from the UK’s standpoint.

Switzerland’s extensive – though not complete – access to the Single Market may be the kind of setup Brussels could agree with London, but the British government’s reluctance to accept freedom of movement makes this one of the most contentious aspects of their negotiation.

In the end, while the Swiss model is flawed, it is on the verge of getting an upgrade. What ought to be of particular interest to London is where the EU concedes ground to Switzerland in its attempt to secure this new agreement.

Interestingly though, the strict time constraints surrounding Brexit negotiations aren’t formally in place for Swiss-EU negotiations. This somewhat turns the tables on the whole question of whether the Norwegian, Swiss or Canadian model best suits Britain.

It looks increasingly likely that the UK will opt for its own particular model of cooperation with Brussels. It could therefore be that Switzerland that adopts a more “British” model, rather than the other way around.

Originally published by Capx,and written by James Holland, writer on European politics. (Find the original article here bit.ly/2G0IoC4)