‘High rents and prices’, ‘foul air’, ‘excessive hours’, ‘closing out of nature’. These phrases might well define some of the urban issues of today, but they were, in fact, written in 1898 by the urban planner Ebenezer Howard to describe the problems in the cities of his time. His solution for the UK was to combine the benefits of country living with those of city living with the creation of ‘garden cities’.

It is clear many of the urban problems of today, including lack of housing affordability and increasing levels of pollution, match those that Garden Cities were conceived to solve. And there has been a revival of interest in this concept as a result, with the Government finding the political space to publish a sustained series of policies on new settlements in a way not seen for 40 years: namely Garden Villages (2016), Garden Towns (2017), and now Garden Communities (2018). The notable absence of the word ‘city’ presumably aims to avoid alarming populations close to where such developments might occur. There has also, partly for the same reason, been a firm emphasis on proposals for new settlements to be ‘locally led’.

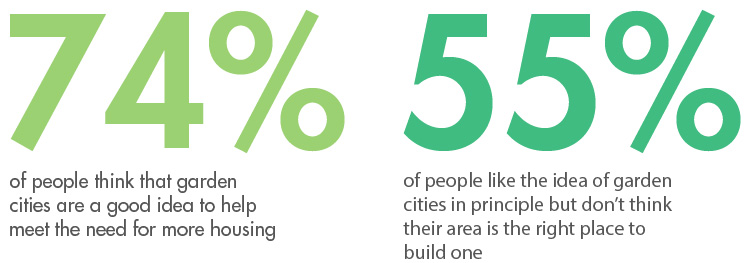

Figure 1: Attitudes to garden cities among the UK population in 2014

Source: Conservative Home (Sample size: 6,000 UK residents)

Despite this new interest, a range of challenges stand in the way of realising the promise of garden cities. These include fractured land ownership, opposition to development, the need for local authorities to cooperate to deliver the required infrastructure, and changing political priorities which make it difficult for ambitious proposals to ‘stick’.

For a totally new garden city to be achieved by 2040, some solution (or set of solutions) needs to be found. And with all of the challenges that we have identified relating to local political difficulties to some degree related to local political difficulties. It follows that these solutions will need to be both political and transcendental of local issues.

Nevertheless, there is some evidence that ‘locally led’ solutions are making progress. In particular, the area beyond the London Green Belt which runs roughly from Oxford to Cambridge has ambitious plans (currently known as the CaMKOx plan). While this area embraces the largest new post-war settlement in the UK (Milton Keynes), it is also intended to create new towns and city growth close to the nation’s housing hotspot: London.

However, significant new housing is often not purely a local initiative: the National Infrastructure Commission, for example has been heavily involved in promoting infrastructure solutions which support housing growth, including in the CaMKOx region. And in 2014, the Government set up a Development Corporation at Ebbsfleet to help support supporting growth.

Garden city and new town fans will know there’s precedent for this. In 1967, a Development Corporation was set up by the Government to build Milton Keynes, but this was wound up some 25 years later. While Milton Keynes is still growing today, it’s first 25 years were enough to make it an economically sustainable city. So, starting today, a similar feat could well be possible by 2040, and the most likely location for it seems to be in the same area once more.