Floating on a sea of money, will asset prices eventually sink – or make landfall on the solid ground of economic recovery?

Global equity markets have performed pretty well in the year to date, even as the world’s major economies are only slowly rebooting from Covid-19. Over the eight months to late August, as we write this, the S&P 500 has risen by 5%, the NASDAQ is up 26%, and the Shanghai Composite up 11%. The Nikkei was down by only 1% and the Dax by 4%, steadily returning to pre-pandemic levels. The FTSE 100 and the Hang Seng performed less well, but these exchanges represent economies suffering substantial damage from other political and geopolitical shifts. Even these have recovered substantially since March, when pandemic-related fears were most intense.

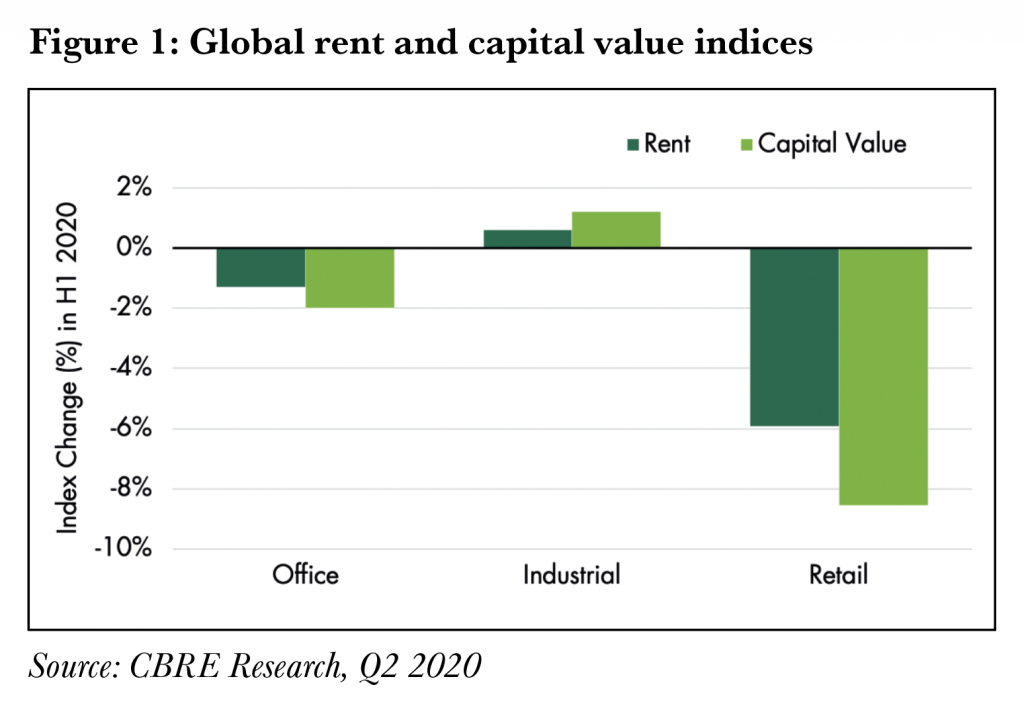

The performance of the prime real estate sector is a bit more downbeat, but not by much. Figure 1 shows CBRE’s latest data on global rents and capital values. In the office sector, capital values have fallen a little more than prime rents, implying a mild cap rate (yield) expansion. For industrial property, rents continued to climb and capital values edged up, implying further cap rate compression. In retail, the decrease in prime capital values outstripped the drop in rents, and cap rates have increased. Prime retail posted stronger gains than other sectors in the 2010 to 2016 period, so some of this drop is reversion to trend.

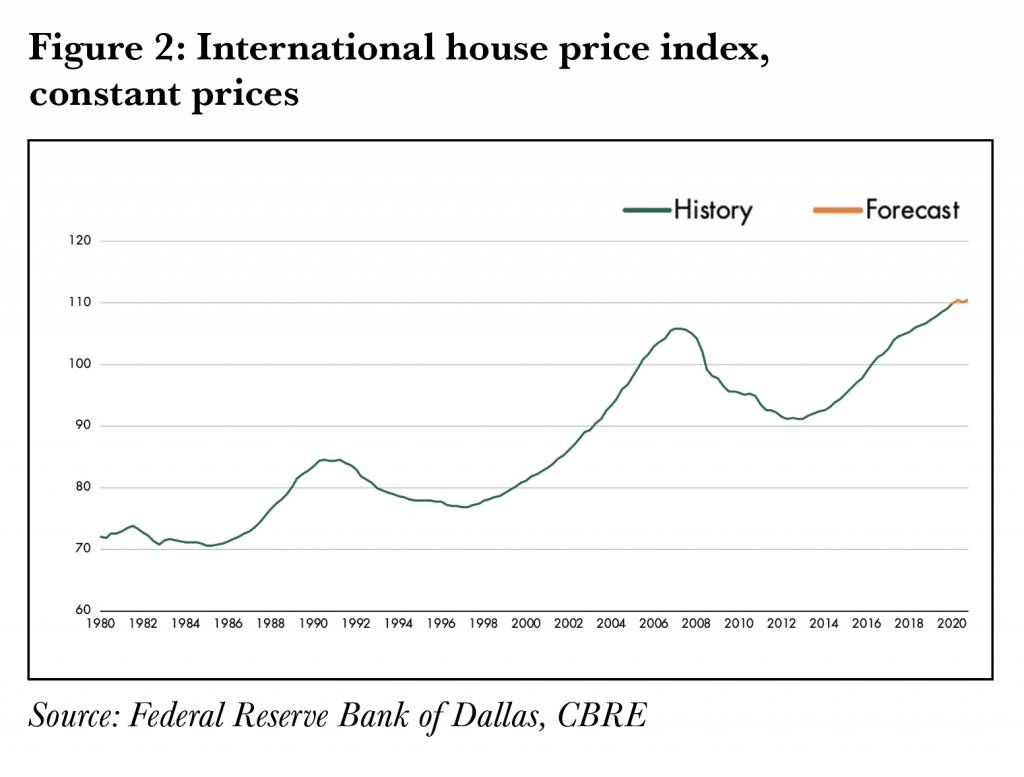

As for residential, the jury is out on apartment/multi-family home pricing. Cap rates for high-grade assets have not increased, but net operating incomes are challenged. There is some evidence that leasing is tough in big cities in the US partly because tenants are taking the opportunity of all-time low mortgage rates to acquire houses in the suburbs. The single-family housing market, which is more significant in overall value terms, is holding onto its value gains of the past ten years and edging up, in the US and elsewhere (see figure 2). Risk-off assets, such as bonds and gold, have also risen in value.

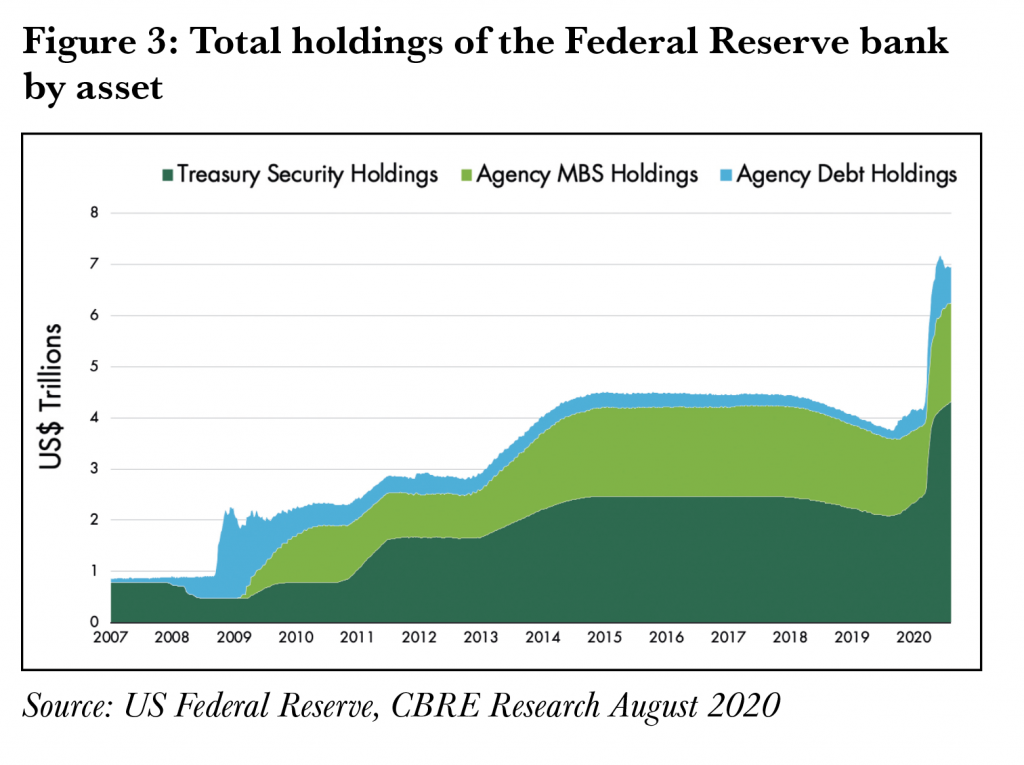

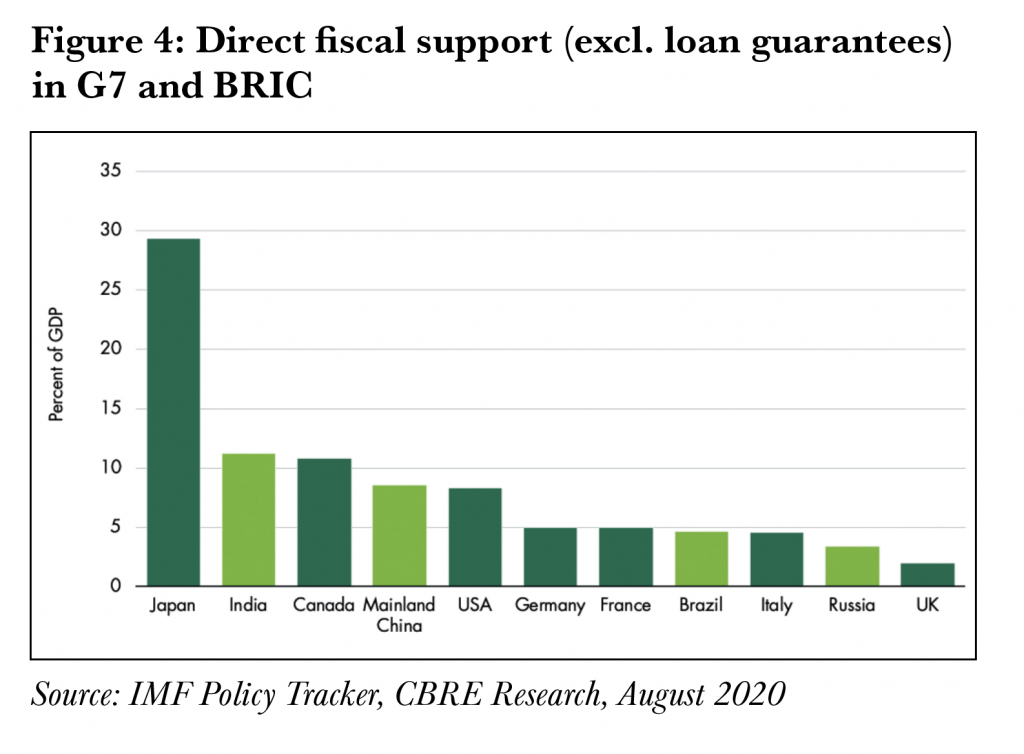

Why, given the severity of the Covid-19 crisis, have asset markets emerged more or less unscathed? The scale and promptness of government intervention, particularly monetary stimulus, is the main explanation. Central banks have responded to the crisis with an alacrity that is almost alarming. Figure 3 shows that the US Federal Reserve employed more quantitative easing in the first three months of the Covid-19 crisis than in the five years after the global financial crisis. As a result, US money supply growth has accelerated to “the highest rate in its peacetime history,” Prof. Tim Congdon of the Institute of International Monetary Research said in June. Figure 4 shows the fiscal stimulus enacted by the G7 and BRIC economies, and there is surely more to come.

An estimated $10bn has been spent on accelerated development and pre-orders of a Covid-19 vaccine, not including China and Russia. And it seems that this has already paid off. At least one vaccine is expected to be licensed by the year end and widely deployed in the first half of 2021. Perhaps more importantly than the specific intervention these efforts seemingly point to an era of greater government intervention in the economy – which is, in a bigger sense, an antidote to a long era of demand deficiency or secular stagnation.

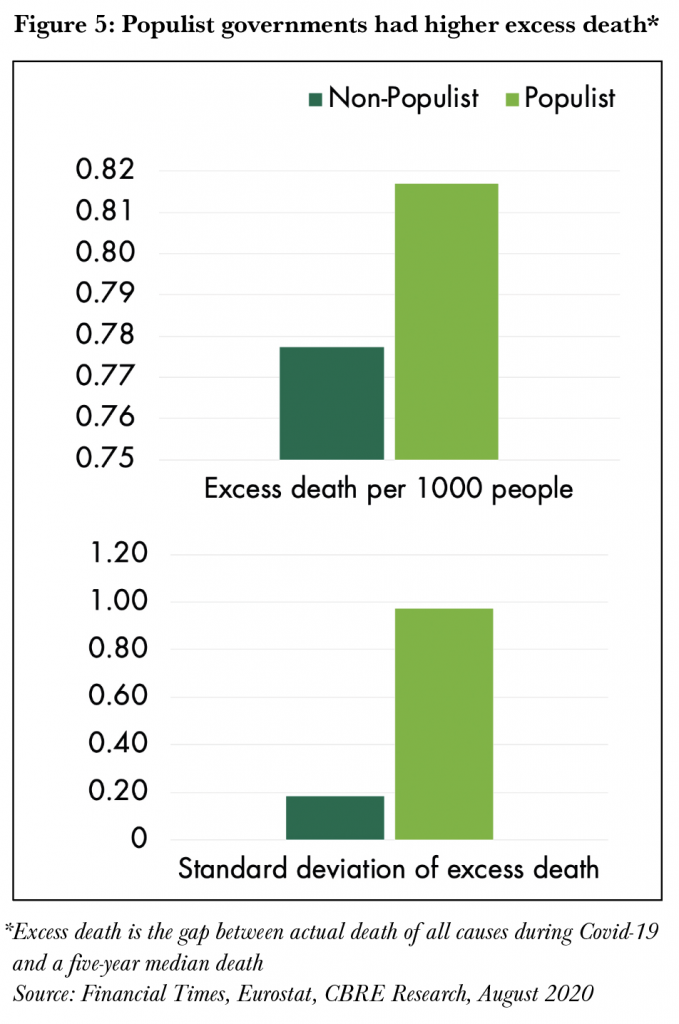

Politics may also have been nudged in a more internationalist direction by the virus, which will put less stress on asset markets through trade tensions. Figure 5 shows that populist governments, as defined by their claims to uphold the will of the ‘true people’ against ‘outsiders’ (as described in the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change’s High Tide? Populism in Power, 1990-2020), have dealt less well with the crisis than have those in the non-populist camp.

All that may be a little speculative, but one thing we do know is that tech has done well out of the crisis. The 26% year-to-date rise of the tech-heavy NASDAQ index points to accelerated growth of the digital economy, alongside life sciences. Reported earnings of leading tech firms beat expectations in Q2 2020 even as earnings in the rest of corporate America fell by 30%. The rise of the digital economy poses some challenges to real estate, but its wealth-creating potential is good for asset values more generally.

Is it really possible to dodge a once-in-a-century pandemic bullet without any adverse consequences for the real economy? Floating on a sea of money, will asset prices eventually sink, or will they make landfall on the solid ground of economic recovery?

Despite the suggestion in the latest US Fed statements that it may be reaching the limit of the current round of monetary stimulus (there will be no cap on long-term interest rates as is the case in Japan), it is reasonable to expect that the Fed’s balance sheet and those of other central banks will be in play for the next 12 months. Globally, policy interest rates are in or heading to negative territory and will stay there for the foreseeable future. However, if the global economy rebounds as expected in 2021, with 5% to 6% GDP growth in the US, we will see volatility as the reversal of monetary stimulus comes into view, even if that reversal is gentle at first.

Is it really possible to dodge a

once-in-a-century pandemic bullet without any adverse consequences for the real economy?

Further fiscal stimulus also seems likely in the US, Europe and Asia, given the electoral cycle and the lingering effect of the crisis. Indeed, common EU bonds issued to aid the EU recovery, secured by common EU tax revenues, are a historic step that will long outlive the Covid-19 crisis. This too has its limits. Governments cannot underwrite salaries for jobs that don’t exist, loans for companies with negative cash flows, and generous unemployment benefits forever, nor will they. By mid or late 2021 governments will be looking to tighten up.

Longer term, the risks become more speculative. When the tech crash happened in 2000 and 9/11 took place, the US adopted super-aggressive monetary stimulus. That had the effect, after several years, of stoking a housing bubble. Something similar might be under way now. Fuelled by the lowest mortgage rates on record, the single-family homes market has rebounded strongly and may be the hottest sector in the US right now (according to Pantheon Macroeconomics’ August chart book). Watch out for a post-covid ‘build, build, build’ (in the words of UK prime minister Boris Johnson) construction boom, with infrastructure in the mix as well.

Even further out, the huge growth of the money supply points to the possibility of a surge in inflation. It is hard to imagine, given the experience of the last ten years and the negative output gap that currently exists. But the rate of growth of broad money over the last decade averaged 4% per annum, whereas between April and June it grew at 100% annualised (according to shadowstats.com). Under these circumstances, indebted Western governments would certainly have to retrench as debt becomes more expensive. Baby boomers nearing retirement will see their pension funds, which are loaded with fixed-income assets, shrink. Real estate cap rates would have to adjust to higher bond yields and might lose the inflation tracking capabilities they once had.

Bottom line, most investors will be surprised if not delighted at how well they have done given the economic consequences of the pandemic. Moreover, asset prices look well-supported for now. However, even if assets land on the solid ground of recovery, that land might be barren and difficult. Investors should be using the current reprieve to go defensive, and that does not mean heading to the bond market. It means extreme diversification and a focus on the digital economy and inflation hedging.