One summer night in August, 1935, a young Soviet miner named Alexei Stakhanov managed to extract 102 tonnes of coal in a single shift. This was nothing short of extraordinary (according to Soviet planning, the official average for a single shift was seven tonnes).

Stakhanov shattered this norm by a staggering 1,400%. But the sheer quantity involved was not the whole story. It was Stakhanov’s achievement as an individual that became the most meaningful aspect of this episode. And the work ethic he embodied then – which spread all over the USSR – has been invoked by managers in the West ever since.

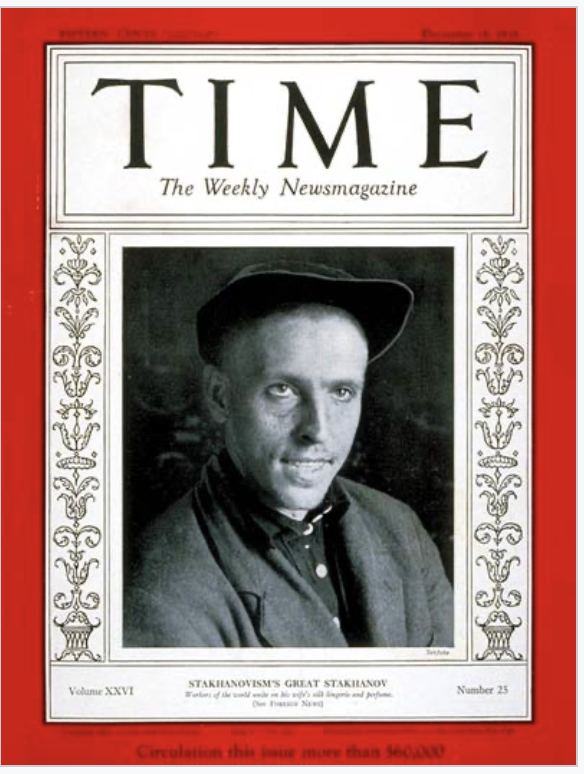

Stakhanov’s personal striving, commitment, potential and passion led to the emergence of a new ideal figure in the imagination of Stalin’s Communist Party. He even made the cover of Time magazine in 1935 as the figurehead of a new workers’ movement dedicated to increasing production. Stakhanov became the embodiment of a new human type and the beginning of a new social and political trend known as ‘Stakhanovism’.

That trend still holds sway in the workplaces of today – what are human resources, after all? Management language is replete with the same rhetoric used in the 1930s by the Communist Party. It could even be argued that the atmosphere of Stakhanovite enthusiasm is more intense today than it was in Soviet Russia. It thrives in the jargon of Human Resource Management (HRM), as its constant calls to express our passion, individual creativity, innovation and talents echo down through management structures.

But all this ‘positive’ talk comes at a price. For over two decades, our research has charted the evolution of managerialism, HRM, employability and performance management systems, all the way through to the cultures they create. We have shown how it leaves employees with a permanent sense of never feeling good enough and the nagging worry that someone else (probably right next to us) is always performing so much better.

From the mid-1990s, we charted the rise of a new language for managing people – one that constantly urges us to see work as a place where we should discover ‘who we truly are’ and express that ‘unique’ personal ‘potential’ which could make us endlessly ‘resourceful’.

Focusing on the ‘self’ gives management unprecedented cultural power

The speed with which this language grew and spread was remarkable. But even more remarkable are the ways in which it is now spoken seamlessly in all spheres of popular culture. This is no less than the very language of the modern sense of self. And so it cannot fail to be effective. Focusing on the ‘self’ gives management unprecedented cultural power. It intensifies work in ways which are nearly impossible to resist. Who would be able to refuse the invitation to express themselves and their presumed potential or talents?

Stakhanov was a kind of early poster boy for refrains like: ‘potential’, ‘talent’, ‘creativity’, ‘innovation, ‘passion and commitment’, ‘continuous learning’ and ‘personal growth’. They have all become the attributes management systems now hail as the qualities of ideal ‘human resources’. These ideas have become so entrenched in the collective psyche that many people believe they are qualities they expect of themselves, at work and at home.

The superhero worker

So, why does the spectre of this long-forgotten miner still haunt our imaginations? In the 1930s, miners lay on their sides and used picks to work the coal, which was then loaded on to carts and pulled out of the shaft by pit ponies. Stakhanov came up with some innovations, but it was his adoption of the mining drill over the pick which helped drive his productivity. The mining drill was still a novelty and required specialist training in the 1930s because it was extremely heavy (more than 15kgs).

The party wanted to create an increasingly formalised elite representing the human qualities of a superhero worker

Once the Communist Party realised the potential of Stakhanov’s achievement, Stakhanovism took off rapidly. By the autumn of 1935, equivalents of Stakhanov emerged in every sector of industrial production. From machine building and steel works, to textile factories and milk production, record-breaking individuals were rising to the elite status of ‘Stakhanovite’. They were stimulated by the Communist Party’s ready adoption of Stakhanov as a leading symbol for a new economic plan. The party wanted to create an increasingly formalised elite representing the human qualities of a superhero worker.

Such workers began to receive special privileges (from high wages to new housing, as well as educational opportunities for themselves and their children). And so the Stakhanovites became central characters in Soviet Communist propaganda. They were showing the world what the USSR could achieve when technology was mastered by a new kind of worker who was committed, passionate, talented and creative. This new worker was promising to be the force that would propel Soviet Russia ahead of its Western capitalist rivals.

Soviet propaganda seized the moment. A whole narrative emerged showing how the future of work and productivity in the USSR should unfold over the coming decades. Stakhanov ceased to be a person and became the human form of a system of ideas and values, outlining a new mode of thinking and feeling about work.

It turns out that such a story was sorely needed. The Soviet economy was not performing well. Despite gigantic investments in technological industrialisation during the so-called ‘First Five-Year Plan‘ (1928-1932), productivity was far from satisfactory. Soviet Russia had not overcome its own technological and economic backwardness, let alone leap over capitalist America and Europe.

‘Personnel decides everything’

The five-year plans were systematic programmes of resource allocation, production quotas and work rates for all sectors of the economy. The first aimed to inject the latest technology in key areas, especially industrial machine building. Its official Communist Party slogan was ‘Technology Decides Everything‘. But this technological push failed to raise production; the standard of living and real wages ended up lower in 1932 than in 1928.

The ‘Second Five-Year Plan‘ (1933-1937) was going to have a new focus: ‘Personnel Decides Everything‘. But not just any personnel. This was how Stakhanov stopped being a person and became an ideal type, a necessary ingredient in the recipe for this new plan.

On 4 May 1935, Stalin had already delivered an address entitled Cadres [Personnel] Decide Everything. So the new plan needed figures like Stakhanov. Once he showed that it could be done, in a matter of weeks, thousands of ‘record-breakers’ were allowed to try their hand in every sector of production. This happened despite reservations from managers and engineers who knew that machines, tools and people cannot withstand such pressures for any length of time.

Regardless, the party propaganda needed to let a new kind of working-class elite grow as if it was spontaneous – simple workers, coming from nowhere, driven by their refusal to admit quotas dictated by the limits of machines and engineers. Indeed, they were going to show the world that it was the very denial of such limitations that constituted the essence of personal involvement in work: break all records, accept no limits, show how every person and every machine is always capable of ‘more’.

On 17 November 1935, Stalin provided a definitive explanation of Stakhanovism. Closing the First Conference of Stakhanovites of Industry and Transport of the Soviet Union, he defined the essence of Stakhanovism as a leap in “consciousness” – not just a simple technical or institutional matter. Quite the contrary, the movement demanded a new kind of worker, with a new kind of soul and will, driven by the principle of unlimited progress. Stalin said:

“These are new people, people of a special type… the Stakhanov movement is a movement of working men and women which sets itself the aim of surpassing the present technical standards, surpassing the existing designed capacities, surpassing the existing production plans and estimates. Surpassing them – because these standards have already become antiquated for our day, for our new people.“

In the ensuing propaganda, Stakhanov became a symbol burdened with meanings. Ancestral hero, powerful, raw and unstoppable. But also one with a modern, rational and progressive mind which could liberate the hidden, untapped powers of technology and take command of its limitless possibilities. He was cast as a Promethean figure, leading an elite of workers whose nerves and muscles, minds and souls, were utterly attuned to the technological production systems themselves. Stakhanovism was the vision of a new humanity.

‘The possibilities are endless’

The Stakhanovites’ celebrity-status offered enormous ideological opportunities. It allowed the rise of production quotas. Yet this rise had to remain moderate, otherwise Stakhanovites could not be maintained as an elite. And, as an elite, Stakhanovites themselves had to be subjected to a limitation: how many top performers could really be accommodated before the very idea collapsed into normality? So quotas were engineered in a way which we might recognise today: by the forced distribution or ‘stack ranking‘ of all employees according to their performance.

After all, how many high-performers can there be at any one time? The former CEO of General Electric, Jack Welch, suggested 20% (no more, no less) every year. Indeed, the Civil Service in the UK operated on this principle until 2019, but used a 25% top performer quota. In 2013, Welch claimed this system was “nuanced and humane”, that it was all “about building great teams and great companies through consistency, transparency and candor” as opposed to “corporate plots, secrecy or purges”. Welch’s argument was, however, always flawed. Any forced distribution system inextricably leads to exclusion and marginalisation of those who fall in the lower categories. Far from humane, these systems are always, inherently, threatening and ruthless.

And so Stakhanovism is still flowing through modern management systems and cultures, with their focus on employee performance and constant preoccupation with ‘high performing’ individuals.

Something that often gets forgotten is that Stalinism itself was centred on an ideal of the individual soul and will: what is there that ‘I’ am not able to do? Stakhanov fitted perfectly this ideal. Western culture has been telling itself the same ever since – “the possibilities are endless”.

This was the logic of the Stakhanovite Movement in the 1930s. But it is also the logic of contemporary popular and corporate cultures, whose messages are now everywhere. Promises that “possibilities are endless”, that potential is “limitless”, or that you can craft any future you want, can now be found in ‘inspirational’ posts on social media, in management consultancy speil and in just about every graduate job advertisement. One management consultancy firm even calls itself Infinite Possibilities.

Indeed, these very sentences made it on to a seemingly minor coffee coaster used by Deloitte in the early 2000s for their graduate management scheme. On one side it said: “The possibilities are endless.” While on the other side, it challenged the reader to take control of destiny itself: “It’s your future. How far will you take it?”

Insignificant though these objects may appear, a discerning future archaeologist would know that they carry a most fateful kind of thinking, driving employees now as much as it drove Stakhanovites.

The rapid proliferation of fashionable management trends follows the increased preoccupation with the pursuit of ‘endless possibilities’

But are these serious propositions or just ironic tropes? Since the 1980s, management vocabularies have grown almost incessantly in this respect. The rapid proliferation of fashionable management trends follows the increased preoccupation with the pursuit of ‘endless possibilities’, of new and unlimited horizons of self-expression and self-actualisation.

It is in this light that we have to show our selves as worthy members of corporate cultures. Pursuing endless possibilities becomes central to our everyday working lives. The human type created by that Soviet ideology so many decades ago, now seems to gaze at us from mission statements, values and commitments in meeting rooms, headquarters and cafeterias – but also through every website and every public expression of corporate identity.

Stakhanovism’s essence was a new form of individuality, of self-involvement in work. And it is this form that now finds its home as much in offices, executive suites, corporate campuses, as in schools and universities. Stakhanovism has become a movement of the individual soul. But what does an office worker actually produce and what do Stakhanovites look like today?

Today’s corporate Stakhanovites

In 2020, the drama series Industry, created by two people with direct experience of corporate workplaces, gave us a glimpse into modern Stakhanovism. It is a sensitive and detailed examination of the destinies of five graduates joining a fictional, but utterly recognisable, financial institution. The show’s characters become almost instantly ruthless neo-Stakhanovites. They knew and understood that it was not what they could produce that mattered for their own success, but how they performed their successful and cool personas on the corporate stage. It was not what they did but how they appeared that mattered.

The dangers of failing to appear extraordinary, talented or creative were significant. The series showed how working life descends into unending personal, private and public struggles. In them, every character loses a sense of direction and personal integrity. Trust disappears and their very sense of self increasingly dissolves.

Normal days of work, normal shifts, no longer exist. Workers have to perform endlessly, gesturing so that they look committed, passionate and creative. These things are compulsory if employees are to retain some legitimacy in the workplace. So working life carries the weight of potentially determining a person’s sense of worth in every glance exchanged and in every inflection of seemingly insignificant interactions – whether in a board room, over a sandwich or a cup of coffee.

Friendships become impossible because human connection is no longer desirable since trusting others weakens anyone whose success is at stake. Nobody wants to fall out of the Stakhanovite society of hyper-performing top talents. Performance appraisals that may lead to dismissal are a scary prospect. And this is the case both in the series and in real life.

The last episode of Industry culminates in half the remaining graduates getting sacked following an operation called Reduction In Force. This is basically a drastic final performance appraisal where each employee is forced to make a public statement arguing why they should remain – much like on the reality TV series The Apprentice. In Industry, the characters’ statements are broadcast on screens throughout the building as they describe what would make them stand out from the crowd and why they are worthier than all others.

Reactions to Industry emerged very quickly and viewers were enthusiastic about the show’s realism and how it resonated with their own experiences. One YouTube channel host with extensive experience of the sector reacted to each episode in turn; the business press too reacted promptly, alongside other media. They converged in their conclusions: this is a serious corporate drama whose realism reveals much of the essence of work cultures today.

Industry is important because it touches directly on an experience so many have: the sense of a continuous competition of all against all. When we know that performance appraisals compare us all against each other, the consequences on mental health can be severe.

What does life feel like when all we have to measure ourselves by are other people’s instant ratings of us?

This idea is taken further in an episode of Black Mirror. Entitled Nosedive, the story depicts a world in which everything we think, feel and do becomes the object of everyone else’s rating. What if every mobile phone becomes the seat of a perpetual tribunal that decides our personal value – beyond any possibility of appeal? What if everyone around us becomes our judge? What does life feel like when all we have to measure ourselves by are other people’s instant ratings of us?

We asked these questions in detail in our research, which charted the evolution of performance management systems and the cultures they create over two decades. We found that performance appraisals are becoming more public (just as in Industry), involving staff in 360-degree systems in which every individual is rated anonymously by colleagues, managers and even clients on multiple dimensions of personal qualities.

Management systems focusing on individual personality are now combining with the latest technologies to become permanent. Ways of reporting continuously on every aspect of our personality at work are increasingly seen as central to mobilising ‘creativity’ and ‘innovation’.

And so it might be that the atmosphere of Stakhanovite competition today is more dangerous than in 1930s Soviet Russia. It is even more pernicious because it is now driven by a confrontation between people, a confrontation between the worth of ‘me’ against the worth of ‘you’ as human beings – not just between the worth of what ‘I am able to do’ against what ‘you are able to do’. It is a matter of a direct encounter of personal characters and their own sense of worth that has become the medium of competitive, high-performance work cultures.

The Circle, by Dave Eggers, is perhaps the most nuanced exploration of the world of 21st-century Stakhanovism. Its characters, plot and context, its attention to detail, bring to light what it means to take up one’s personal destiny in the name of the imperative to hyper-perform and over-perform one’s self and everyone around us.

When the ultimate dream of becoming the central star of corporate culture comes true, a new Stakhanov is born. But who can maintain this kind of hyper-performative life? Is it even possible to be excellent, extraordinary, creative and innovative all day long? How long can a shift of performative work be anyway? The answer turns out not to be fictional at all.

Stakhanovism’s limits

In the summer of 2013, an intern at a major city financial institution, Moritz Erhardt, was found dead one morning in the shower of his flat. It turns out that Erhardt really did try to put in a neo-Stakhanovite shift: three days and three nights of continuous work (known among London City workers and taxi drivers as a ‘magic roundabout‘).

But his body could not take it. We examined this case in detail in our previous research as well as anticipating just such a tragic scenario a year before it happened. In 2010, we reviewed a decade of the Times 100 Graduate Employers and showed explicitly how such jobs can embody the spirit of neo-Stakhanovism.

Then in 2012, we published our review, which signalled the dangers of the hyper-performative mould promoted in such publications. We argued that the graduate market is driven by an ideology of potentiality which is likely to overwhelm anyone who follows it too closely in the real world. A year later, this sense of danger became real in Erhardt’s case.

Stakhanov died after a stroke in Donbass, in eastern Ukraine, in 1977. A city in the region is named after him. The legacy of his achievement – or at least the propaganda that perpetuated it – lives on.

But the truth is that people do have limits. They do now, just as they did in the USSR in the 1930s. Possibilities are not infinite. Working towards goals of endless performance, growth and personal potential is simply not possible. Everything is finite.

Who we are and who we become when we work are actually fundamental and very concrete aspects of our everyday lives. Stakhanovite models of high-performance have become the register and rhythm of our working lives even though we no longer remember who Stakhanov was.

The danger is that we will not be able to sustain this rhythm. Just as the characters in Industry, Black Mirror or The Circle, our working lives take destructive, toxic and dark forms because we inevitably come up against the very real limits of our own purported potential, creativity or talent.

Originally published by The Conversation and republished here with permission.