This article was originally published in October 2018.

The returns on most investments are purely financial. But some investments have other rewards. Buying art, for instance, offers the chance not only to anticipate what is going to do well, but to exercise your taste, look for something you appreciate, and enjoy it for as long as you like before selling it – if others appreciate it too – at a profit. The poet Stephen Spender and his wife Natasha often bought pictures, and since they moved in creative circles and counted the sculptor Henry Moore and the artist John Piper among their friends, some of the pieces they acquired became very valuable. Occasionally they would sell one because they needed money, but they would devote part of the proceeds to buying from promising younger artist-friends such as David Hockney.

Collecting is not only fun but an education. All collectors make mistakes, especially early on, but things you find you don’t want can be sold, and you soon learn that the ones you regret–perhaps for the rest of your life–are the ones that you didn’t buy. As a book dealer once advised me, “Only buy the things you can’t afford.”

The more expert you become, the more discriminating you will be, and the greater the chance that you will buy well, because you know something or can see qualities that the vendor does not. You may recognise a maker’s mark on a piece of furniture or a potter’s characteristic use of colour; you may decipher a signature in a book and understand why its provenance is important; or you may know how exceptionally rare a particular Dinky toy is, because it was one of the earliest. There is an expertise that can only be acquired from the experience of handling many objects, discovering their history, how they were made and what they tell us about their own period. At a sale viewing once, a friend of mine found a tiny piece of paper inside a harpsichord which turned out to be the invoice from a very famous maker. Sotheby’s hadn’t noticed. He tucked it back and was very pleased with his purchase.

But beyond collecting there is a further imaginative step, which is to commission something new from an artist or craftsman. This requires time and commitment as well as cash, but can give a special sense of fulfilment because the work is partly your own creation, the fulfilment of a conception of your own. Commissions are crucial investments in traditions of workmanship that make originality possible, expressions of trust not only in an individual sculptor, silversmith, cabinetmaker or glassblower, but in the future of the trade or art. And trust in the collaboration is very important. “I need to have confidence that the client has confidence in me,” says Hugh Wedderburn, Honorary Secretary of the Master Carvers’ Association.

The impulse to commission can come in various ways. You may admire the work of a particular maker; you may be marking an occasion; you may need new curtains and want to have a special design woven; or you may want a gift of jewellery to embody a personal story.

If you don’t have a maker in mind, it may be useful to contact a trade association such as the British Woodworkers’ Federation, Memorials by Artists or one of the ancient guilds such as the Goldsmiths’ or Carpenters’ Company. Before you commit yourself, make sure you meet the individual craftsman (is this someone you’d like to work with?) and see his or her work close up (never merely on screen). Hold the work, inspect it from all angles; imagine how your idea might take shape if this craftsman undertakes it.

The degree of clients’ involvement varies a lot, says Wedderburn. “One will simply ask for a chair with a touch of the Orient about it and leave me to it, whereas another client, who has commissioned from me frequently, is involved throughout. It can take years before we get as far as a drawing, and she makes regular visits to the workshop.” Commissioning can take time, so don’t be surprised if you are asked for part-payment up front.

Abundant Harvest by Hugh Wedderburn

When discussing what you have in mind, the better you know how the craftsman works – characteristic materials, designs, techniques and styles – the more likely it is that you will speak the same language. “The patron comes with an idea which I have to fathom and make practical,” says Wedderburn. “They have to understand my limitations and what wood can do. It’s not a compromise, but we have to find mutual territory, so that my work can express their vision.”

Whether it’s a festive mural for your dining room or a modern designer bookbinding, you should live with a rough sketch for a while first. Then ask for a fully developed drawing, so you can see how it is being realised in the maker’s imagination. I once commissioned some pen-and-ink book illustrations from the artist David Gentleman, and I remember my surprise when I visited and found the sketches strung along a washing-line, from frontispiece and title-page through to the tailpiece. Each peg held three or four successive drawings, most recent at the front. So here was a series of drafts for each image, for me to inspect and compare.

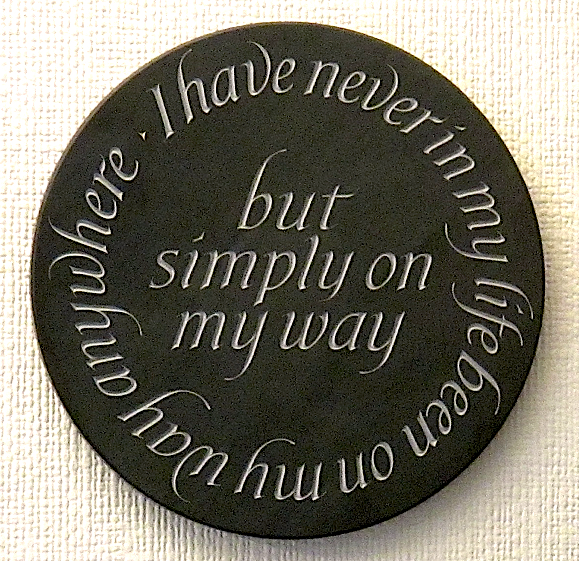

As well as wood-engravers and fine press printers for my little publishing enterprise, I have had the pleasure of commissioning a calligrapher and a young portrait painter, as well as a bowl from the glass-engraver Laurence Whistler, and an inscription in a circular slate from the lettercutter Lida Kindersley. At present, I’m considering commissioning a small stained-glass memorial pane — featuring a possum!

Many craftsmen receive the bulk of their commissions from institutions, so working for a private client can have an extra aspect of challenge and friendship. Wedderburn’s workshop is Southwark, within strolling distance of St Paul’s, where some of the finest work by Grinling Gibbons, the most famous of all British wood carvers, is found. Hugh has done a lot of conservation and restoration work on 17th and 18th-century pieces for charities, antique dealers and guilds such as the Haberdashers–a splendid pair of goats–so he was pleased to be asked to carve a trophy on musical theme by a private client (“No committees to deal with!”) Carved in limewood for a house in a London square, the piece represents the setting as a sanctuary; so as well as violin, bow and flute, it features, birds, a frog and snails amid the foliage and fruit. “There is some homage to Gibbons in the foliage,” he says, “but this one is pure Wedderburn.”

Other recent work includes roundels with heraldic bas relief carving in a pair of parade chairs used for Trooping the Colour by Queen and Duke of Edinburgh, and a chimney-surround with motifs from shooting: mouldings of poppies, acorns and woodcocks. Next in line is a trip to the convent in Parma to see the rams’ heads depicted in Correggio’s frescoes, which a client wants carved as curtain rod finials to be cast in bronze.

Remember, the final work is never quite how you envisaged it. There are always technical issues that you hadn’t anticipated, and which the craftsman will simply resolve by instinct and training. However precise your instructions, a commission is a collaboration, and you are not the one whose hands hold the knowledge.

Price is usually negotiable, since every case is individual, but remember that part of the point of the exercise is to be a patron, buying the craftsman time to create something for you, and perhaps training the next generation too. Wedderburn’s trophy took eleven months to carve, but the client refused to pay. He sold it elsewhere in an hour. The investment brought something magnificent into the world, but someone else is enjoying the fruits — and the little creatures and the instruments.