Have we got the policy settings right?

In modern societies action against crime is un-coordinated.

Strategies to deter crime are a jumble of public resources (largely funded by the taxpayer) and private action, funded by private citizens who will, often, also be taxpayers or property owners.

Considering the substantial costs, public and private, direct and indirect of these crime limitation activities – and the costs incurred when all-too-often actions to defeat crime fail – it is surprising how scant is the analysis of the cost-benefit trade-offs arising from these strategies. Indeed, in passing laws that create new crimes and in dispensing punishments for old ones Lord Keynes might have said that politicians and judges “hear voices in the air… distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

Something more than an “academic scribbler” was Gary Becker (1939-2014, Nobel Economics laureate 1992). Becker is the founder of the economic analysis of crime and punishment. His austere mathematical models do not aspire to capture all features of public and private policy problems arising from crime. But Becker’s analysis does offer a coherent agenda for an informed debate, encouraging further exploration. A decade after death Becker continues to challenge us to test new ideas and to revisit old ones.

The cost of crime is under-estimated

The direct cost of crime to victims (such as stolen property or medical treatment for injuries) can be calculated in theory but this is likely to be only a tiny portion of the actual cost of crime more broadly defined. The threat, not the crime itself, is probably the most costly aspect of crime. The property owner must then embark on an arms race of protection and surveillance equipment.

How much crime do we want…it’s our choice?

How little crime (or how much safety) are we willing to pay for? Following the Gary Becker analytical approach, the propensity to commit crime or “demand for crime” (DC) by the typical villain might be expressed as some function along the lines of

DC = f ((Expected Dollar Reward) minus (Expected Penalty x Probability of Being Apprehended))

We know very little about the parameters of this function, although Becker does suggest that crime incidence might be quite sensitive to the probability of being apprehended and punished.

The savage penalties visited upon the poor widow caught stealing a potato in the 18th and 19th centuries might then be explained by the fact that while the reward from this crime was small, so too was the probability of arrest. So the cost-effective way to reduce street crime, as Becker prescribes, was to impose very tough penalties. Some petty thieves were even transported at public expense to Australia.

The cost of unpunished crime is high

Resources allocated to the police are often public information set out in government budgets. They are therefore subject to management, even cost-cutting, by quick-win politicians who often live elsewhere. The indirect costs imposed on society and the victims, social and financial, of such economy measures are less readily identified but easily ignored. If the police choose not to act against small time shop lifters, the onus then falls upon the shopkeeper. Understandably, the object is to protect the assets of the business, not those of the retailer next door – who must take similar, perhaps more costly, action in self-defence.

Externalities to crime against retailers can be partly internalised by enclosed shopping mall managers. Less so on the High Street. So the relative costs to do business for High Street retailers rise. Retailers retreat to the shopping malls where the rents may be higher, but security and “shrinkage” costs are less. The High Street becomes bleak and unwelcoming, empty and even sinister – many sad real-world examples attest to this.

Do the Home Office bureaucrats, the judges and police administrators, who allocate resources and set crime deterrent priorities and penalties, subscribe to Becker? Are they as Lord Keynes might have asked: “the slaves of some defunct economist”?

Positive strategies to limit crime

Analysis of crime as a cost-benefit problem stimulates consideration of alternative strategies to combat crime. For example: How to deal with the prolific (but often quite innocuous) graffiti that pollute public spaces?

Police patrols are costly and cameras ineffective because the offenders probably wear face masks. Most graffiti are victimless and therefore hardly worth pursuing. Tougher penalties for those unlucky or stupid enough to be caught red-handed may be a modest deterrent. A tax on spray paint cans, the proceeds to support clean-up costs, would be cumbersome, encourage a black-market, penalising innocent citizens and trades people.

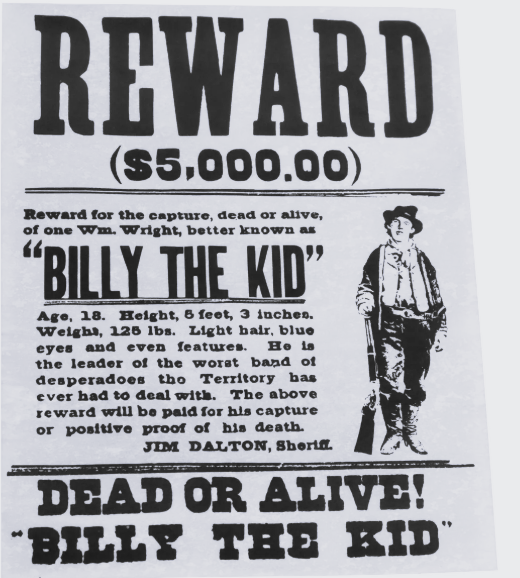

Happily, there is a positive action that might be employed to combat this public nuisance. And Tim Dalton, the Sheriff in the graphic at the head of this column clearly anticipates Gary Becker.

Punishment is a negative incentive. How about a positive incentive?

Consider a generous cash reward (tax free) for information leading to the arrest and successful prosecution of the graffiti artist – the whistle-blower’s identity to remain confidential?

This puts the heat on the offender, not the police. Are his or her associates trustworthy? What about Fred, a gang member’s elder brother – he probably knows what you were up to on Saturday night and he is short of cash at the moment after his speeding fine down the M4? Boasting to your mates about your late-night exploits as you drive past that defaced road sign suddenly becomes risky.

The cash reward is admittedly a direct financial cost to the police or property owner, but perhaps less costly than the costs to patrol the area and repeatedly replace the road signs.

The Billy the Kid poster heading this column (authentic or not) exemplifies the Becker equation.

Strategies for crowded prisons

Policies to deter crime depend heavily on:

- Proposition I: punishment, for example a fine or a prison sentence, deters crime, and

- Proposition II: the more severe the sentence the greater the deterrence, either to the offender or as a demonstration to prospective copy-cat activists.

If these Propositions are incorrect, if punishment does not deter crime and if tougher penalties do not discourage crime further, the entire structure of all legal systems, globally, for the last few thousand years rests on a false foundation.

Right now prisons in the UK reportedly have a problem with overcrowding, leading to pressure on judges to impose shorter sentences and early release for some prisoners, even those with grievous criminal records.

But if prison is indeed a deterrent then reducing sentences and early release might lead to an increase, not a reduction, in the demand for prison accommodation. An economist must ask, what is the elasticity of the demand for crime?

Suppose sentences were doubled in length and early release abolished? Will this lead to more, or to less, prison over-crowding?

You have to agree that under this proposal the incidence of crime will fall. Longer sentences must mean less crime. But by how much? If penalties double but crime rates fall to less than half the result will be fewer, not more, overall days in prison and less, not more, overcrowding.

The elasticity of demand for crime is an empirical question and the elasticity for different types of crime is likely to vary. For example a doubling of penalties for petty theft and shoplifting combined with effective policing might see a big drop in this activity. Crimes of domestic violence might be less responsive to harsher sentences.

We simply don’t know.

Why not experiment?

Without answers to these questions, choices regarding police resourcing and punishment do not go beyond wild guesses. Even a simple experiment might be informative.

Say: double all penalties for knife crime for an initial and experimental period of twelve months and make custodial sentencing mandatory, even (or especially) for first offenders. Advertise this trial widely in advance and publish regular data on locations, incidents and penalties. This needs to be a national experiment, else stabbings will simply shift from Tooting to Wandsworth.

Does knife crime incidence rise or fall? Overall, are more, or less, prison days required? Let’s have a daily scorecard.

Police surveillance shifts from the High Street to the website. Meanwhile, no ex-ante cost-benefit accounting is provided by the police, nor required from the busy lawmakers. There seems to be no systematic ex-post analysis of the cost effectiveness of laws, or the penalties that are assigned to them and then erratically dispensed by congested courts.

Meanwhile the responsibility for deterring crime steadily shifts away from the public domain. High on the list of losers in this game of pass-the-parcel are taxpayers, homeowners and small businesses, as well as real estate investors, tenants and landlords.

This article was originally published in the Spring Issue of The Property Chronicle.