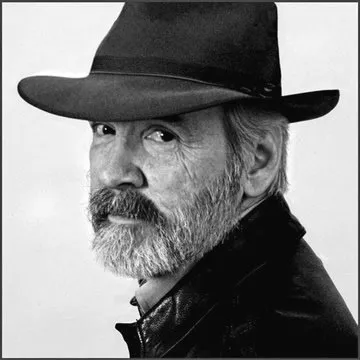

I had a friend from my time living in Sag Harbor who is sadly gone from us now, Anthony “Tony” Brandt, who was married to my equally good friend, Lorraine Dusky.

I bring up Tony today because he and the way he lived his life illustrate what is so different about us – me and Tracy and Tony and Lorraine and you and yours – and what we are constantly told is the ever-encroaching power, or threat, or utility – we’re always being told something different – of artificial intelligence, or AI.

Tony was a man of books, thousands and thousands of books, which he had acquired over his lifetime. Walking into his and Lorraine’s home on High Street in Sag Harbor was like entering a library. Every wall was covered with floor to ceiling bookshelves. There were more on the glassed-in porch on the front of the house, as well as piles of them out there, and more upstairs in his study, and more in the downstairs extra bedroom, and no doubt more in rooms I had not been in.

Nearly every time you walked into the house, Tony was in an armchair in the living room across from the couch under a lamp, reading. He wrote several books of his own and for years was a journalist writing for Esquire, Connoisseur, The Atlantic, American Heritage, Military History magazine, Psychology Today, and for years, he wrote the books column in Men’s Journal. You could see among the titles what his interests were – lots of American and world history, a complete personal library on Jefferson, military matters including history, tactics, and strategy, and apparently every other book that caught his eye at the yard and estate sales that proliferated in the Hamptons during the summer.

I wondered over the years what Tony did with all those books besides read them. It was clear that they informed his own writing, but there were so manyof them it was obvious that he had not collected them for a specific purpose. He had accumulated and read those books because they made him who he was. Any conversation with Tony contained stuff from his books – not the kind of self-conscious specific references that scholars are wont to make; he made casual note of something he had read that touched on the subject at hand. The general sense you got from talking with him, which I spent hours doing over the years, or simply being around him was that he was not a man of literature so much as he was a man of knowledge which he accumulated right along with his books. His library was as extensive as he was fascinating to be with.

But it was more than knowledge he took from all those books. He took from them not only facts and scholarship and analysis. He gathered up what the books’ authors had to say about their subjects and the world around them, the ineffable sensibility and intelligence that went beyond facts, even beyond the subjects the authors wrote about.

There is the word: intelligence. It doesn’t come just from the words printed on paper between covers. It comes from within the writers, and when their books are good – and most of those Tony had chosen for his shelves were very good – what is within the writers translates into the reader, into Tony. That is why what Tony took from his thousands of books could only be described as ineffable, because it was beyond description except by his presence, the selfof Tony Brandt.

It’s also why artificial intelligence will never be the threat to humankind that so many people apparently think it will be. The subject of AI popped up last week with the publication of the RFK Jr. MAHA report that had the subhed of “Make Our Children Healthy Again,” (emphasis in the original.) As you probably know by now, the report was rife with studies that turned out not to exist, and in one case, an author of a study who was made up. As Rolling Stone helpfully summed up, “The MAHA Report was also riddled with broken links, incorrect authors, and other erroneous attributions.” The conservative think tank, the CATO Institute, of all places, went further, concluding that “The data in the report bears little relationship to its conclusions.” All the coverage of the MAHA report pointed out that at least some of the citations appeared to have been generated by artificial intelligence, with some of them containing the telltale notation, “oaicite,” connoting something generated by ChatGTP, which is owned by OpenAI.

So, here we have what was intended to be a landmark study that featured “authors” including the Secretaries of HHS, Education, HUD, Veterans Affairs, EPA, and Agriculture, in addition to Russell Vought, the director of Office of Management and Budget, and Stephen Miller, the White House all-the-time-and-everywhere-jack-of-all-trades adviser on everything from immigration to national security to the budget. The report is a mess because of arrogance and laziness on the part of RFK Jr. and other “authors” who not only couldn’t bring themselves to take the time to study the subject matter, but did not even read the report once it was published.

And AI was right in the middle of the whole thing.

I read a good description today of what artificial intelligence is by Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo.

“AI is being built, even more than most of us realise,” Marshall wrote, “by consuming everyone else’s creative work with no compensation. It’s less ‘thought’ than more and more refined statistical associations between different words and word patterns.” He goes on to make the salient point that the AI “products” being produced will be “privately owned and sold to us.”

Which happened to me today, as a matter of fact. My Google Mail account recently became infected with some sort of AI product owned by Google called “Genesis,” which provided me each and every time I began an email with this unwanted prompt: “Help me write Alt+H.” I didn’t wanted to be so prompted, and so I went looking on the internet for how to cause the prompt to go away, which took me down a rabbit hole of solutions involving the “settings” tab of Gmail. I unclicked everything they suggested to no avail. The prompt refused to go away. And today, I discovered why. A new message in a little box appeared within the Gmail page notifying me that my “trial” use of Genesis on Gmail was about to expire, but I could buy the service by clicking “here.” I hit “cancel” and look forward to the day that my Genesis trial will be over so I can write emails without being asked if I want “help.”

Doubtlessly, what Genesis has been doing is recording every email I have ever written and preparing what Marshall called the “statistical associations between different words and patterns” so they could provide me with suggestions for sentences that would appear to echo my email “style” (or whatever) from before. As if what I want to do is write every new email so that it is similar to every other email I have already written.

That is just one of the massive holes in AI – the assumption that what human beings want to do is repeat themselves, which in my experience over the last 70 years or so is exactly 180 degrees from what I have observed human beings wanting to do. Fashion, for just one example, would die if people wanted to put the same clothes on every day. So would supermarkets and restaurants, which are in the business of offering you new and different choices for what to cook or eat.

But the weakness of AI goes way beyond its obvious basis in repetition and the apparent tendency of AI to “hallucinate” facts and references when there are none, as shown in the MAHA report.

AI will never be able to feel. AI will never, in short, be Tony Brandt. AI will never be able to take all that information from all those books on Tony’s shelves – and there is evidence that is exactly what AI companies are doing by copying information from books and magazines and internet sources into huge databases from which they can generate their repetitive “help” for us today and in the future.

AI can copy all the sentences and words it wants, but it will never be able to achieve anything resembling something as simple as emphasis – that is, synthesising the information and applying experience from a human life to choose which fact or what “study” is more important than another except by using statistics or by emphasis according to repetition and usage, by applying numbers to create “solutions” that would in a human being come from within.

Ask yourself this: of the books or articles or poems you have read, or the music you have listened to, or the movies you have watched, what changed you? The assessments made by AI will never be changed except in ways that can be expressed mathematically within its system, by counting things and adding them up, or assessing the importance of something by what it costs – if it’s more expensive, it’s better; if it’s cheaper, it’s not worth as much.

There is also the matter of changing one’s mind. If you assess something and come to a conclusion based on the information you have, and then you come upon new and different information, you may change your mind about the subject. AI can presumably do this by accumulating information, adding to it, and changing because of the added information.

But what if your assessment is one of what might be called a human value? In my life, I have personally seen people who had been racists since childhood change their beliefs about Black people because of their lived experience knowing and working with them, or by becoming friends, or even falling in love with someone of a different race. How does AI factor that into its computations?

Because that’s what we’re talking about in the end: mathematical computations. If you use this word after that word again and again, it becomes either your common usage or your style. But words arranged in patterns can be serious, or ironic, or sarcastic, or even funny. Math doesn’t work with patterns to achieve humour or sarcasm. Math achieves repetition because it has been taught to apply a value: repetition is good, so use again.

Which is as good a definition of humanness in the accumulation of knowledge in the form of words as I can think of, other than in this way: Tony Brandt. Every time I walked into his house on High Street in Sag Harbor, I knew the experience would be different, because Tony would have read a new book or books, or something in the New York Review of Books, or a column in the Times, or a poem in the East Hampton Star, or even something in the tide tables of the Sag Harbor Express that changed him in some way that would delight me and Tracy and the rest of us in new and wonderful ways.

Let’s see AI try to replicate that.

This article was originally published in the Lucian Truscott Newsletter.