Trump 2.0 is not playing out as billed in last year’s election – is it going to be Wall Street over Main Street yet again?

For about a week in April, the Trump administration did what it said on the tin – gung ho on America First via tariffs, reshoring, making the world pay for the blanket of freedom and so on, all to help reinvigorate American industry, and through this, the plight of the average American worker. Then the bond market and the stock market folded, and it all got put on hold.

When the tariff implementation was paused, the stock market rejoiced and bond yields fell. Since then, very little progress seems to have been made with respect to trade talks, and it now seems that tariff negotiations will either be part of a series of rolling delays or implemented without agreement at much lower levels than initially estimated.

Yet it is in domestic economic policy that the Trump administration’s new direction is becoming clearest. While catnip to the stock market in the short term, what is most concerning is the shift towards fiscal dominance, and particularly what is being said about the Fed, the Fed chairman, and the future direction of interest rate policy.

The New York Stock Exchange. Once again, it all seems to be about asset prices (Photo source: Financial Times / Reuters).

It is abundantly clear that President Trump wants the Fed to cut rates, but this is not out of concern that monetary policy is too tight and that he fears the economy is about to plunge into recession. After initially demanding a 50 basis point cut, President Trump is now calling for 1% Fed funds rates, as well as for Fed Chairman Jay Powell to resign¹.

This is the very definition of the motivation and implementation of fiscal dominance by the executive over the central bank and monetary policy. The motivation for the rate cut is not inflation but reducing interest payments to allow more fiscal spending. The attack on the person of the head of the central bank, with the prospect of a more compliant candidate to replace Mr Powell in 2026, also speaks of institutional capture.

In addition, and in part because Mr Powell isn’t doing Mr Trump’s bidding by not cutting interest rates, the President said on Fox News this past weekend that he’d prefer to start issuing more T-Bills than longer-dated bonds, adding, “I don’t want to have to pay for 10-year debt at a higher rate”.

The risk of a dramatic shift to shorter-dated issuance would of course be a loss of price discovery and market liquidity at longer maturities. The swaps market is of far greater size than the government bond market in notional terms, and any disruptions would inhibit banks and businesses in issuing and hedging their risk. It also means that with more bill issuance, the Fed dictates the interest rate at which the Treasury issues bonds – great if you’re an administration with the Fed in your pocket, but not so great for broader market function.

Shifting US government funding to shorter-dated maturities is not a new policy. Janet Yellen, Secretary of State for the Treasury under Trump’s predecessor, did exactly the same thing. This was doubtless a reflection of the lack of appetite for longer-dated bonds given the huge stock of US debt.

The Treasury debt buy-back programme, initiated under Yellen but substantially ramped-up in quantity under her Republican successor Bessant, also reflects a real supply/demand problem. With lower long-dated issuance and higher buybacks, the Treasury already seems to be elbow-deep in the pickle jar of yield manipulation.

But issuing T-Bills is also great for liquidity and lending. When T-Bills are put up as collateral, their shorter duration and lower risk means a smaller haircut to their nominal value, so more can be lent against them than would be the case for 10-year Treasury notes for example. This is what the credit and especially the stock market loves.

Add in bank capital reforms to allow more bank purchases of government paper and likely policy changes to encourage more stable-coin issuance (backed by T-Bills of course), then you have higher T-Bill demand and higher market liquidity². Great for the Treasury, probably great for risky assets, but at what price?

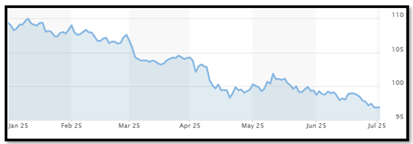

The DXY dollar index – the release valve for fiscal dominance (Photo source: Market Watch).

Year to date, the DXY dollar index is down nearly 11% at the time of writing. Attacking the Fed Chair, demanding rate cuts, talking about bill issuance over bonds, continuing to run huge deficits through spending bills which front-load tax cuts and delay expenditure cuts, as well as the general uncertainty of President Trump’s impulsive diplomatic style, all contribute to dollar weakness. But the stock market is back at the highs, so we’re all cool right?

Since the financial crisis of 2008-9, ‘American exceptionalism’ has taken the form of superior stock price performance relative to other countries. Yet with the S&P 500 up 5.4% year-to-date in dollar-terms, it is down 7.75% in euros, 3.7% in sterling and 2.8% in yen terms.

With the reality of fiscal dominance, the dollar may well continue to trade poorly, making the US an increasingly tough sell to foreign investors and asset allocators. This is before we factor in other Trump policy initiatives that may yet also punish foreign investors.

At the same time, you have the ECB pushing the idea of new euro-denominated savings instruments³, and in the UK, a similar initiative from the government to encourage UK pension funds to invest more in UK equities and UK infrastructure projects⁴. These are just two examples of the pressure on capital flows in a period of economic history which is shifting from globalisation to national particularism. International asset allocation trends will be the real test for American exceptionalism.

The repatriation of savings and investments is something briefly witnessed in the US market sell off in April. A strong stock market bounce may yet be hiding similar long-term undercurrents, especially if a weaker dollar trend continues to the backdrop of a very fully-valued US stock market.

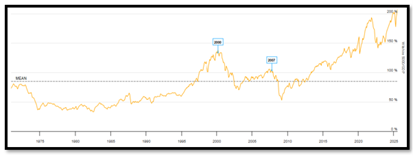

The graph below shows the ‘Buffett indicator’ of US stock market capitalisation to GDP – not a timing tool of course, but a good yardstick when measuring the cheapness of otherwise of US equities.

US stock market capitalisation to GDP – historic highs (Photo source: longtermtrends.net).

As ever, it seems to be a choice between chasing the short-term trend (higher) and being cautious about the medium- to long-term outlook for both the dollar and the US stock market, especially given the high valuations and narrow market breadth currently on display in the latter.

The question isn’t so much how much good news is priced in, but how little bad news has been. Last week for example, we had the US on the verge of war with Iran, and now that’s as good as forgotten. Amazing stuff, really.

For investors, the stakes are high. Is the stock market really on firm ground, or is the Trump administration just teeing up one last great hurrah for the post-financial crisis asset bubble?

References

1

Trevor Hunnicutt & Kanishka Singh, Trump says he wants interest rate cut to 1%, would ‘love’ if Powell resigned, Reuters, 27/06/2025.

2

Pete Schroeder, Fed’s Bowman eyes broad set of bank capital reforms, Reuters, 23/06/2025.

3

Elena Banu et al, Crossing two hurdles in one leap: how an EU savings product could boost returns and capital markets, The ECB Blog, 27/06/2025.

4

George Parker & Mary McDougall, UK confirms powers to force pension funds to back British assets, Financial Times, 29/05/2025.

This article was originally published by Market Depth.