Other things equal, a higher valuation for an asset should make it less attractive.

Returns are being pulled from the future to the present. So why does the reverse often seem to be true? Why do investors often behave as if their return expectations are increasing alongside valuations? *

It is easy to characterise this phenomenon as simply characteristic performance chasing behaviour. Many investors don’t really care about the valuation of an asset; they are focused on recent returns – either attempting to capture momentum or crudely extrapolating the past into the future. Yet while these types of investors are not valuation-driven, changes in valuation are exerting a significant influence on their decisions.

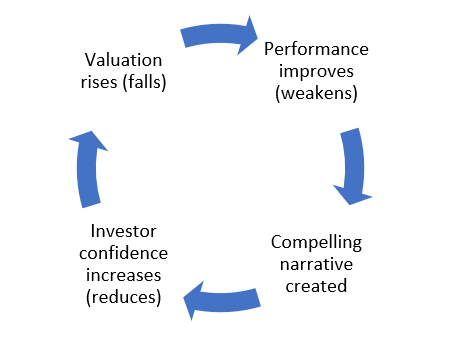

Changes in the valuation of an asset can create self-reinforcing valuation loops – where a rising (falling) valuation directly leads to an increase (decrease) in investor confidence. It looks something like this:

A rising valuation boosts performance; stories are created to justify the strength of performance and this in turn increases investor appetite for the asset thereby increasing the valuation. And so, it can continue.

Let’s take the example of US equities over the past decade. A substantial portion of its outperformance has been due to this market becoming more expensive (alongside good fundamental growth). This rise in valuation inevitably played a role in the emergence and persistence of the ‘US exceptionalism’ argument. As the market became more expensive it became more exceptional.

Ultimately, investors care more about performance and less about what is causing it.

But there must be a limit to these valuation loops, surely the value of an asset can’t keep going in one direction? While there usually is a limit, the strength of it depends on how much of a valuation anchor an asset class possesses.

A valuation anchor is simply some fundamental features of an asset that exert a form of gravitational pull on how cheap or expensive it can become. There are three key factors that dictate how much of a valuation anchor might be apparent:

– Does it have cash flows or any other fundamental means of valuation?

– Are cash flows contractual / constrained?

– Is there a maturity point or is it perpetual?

For example, an ‘AA’ rated corporate bond with two years to maturity has a very strong valuation anchor. Its cash flows are contractual, and it will mature in twenty-four months. There is only so far its valuation is likely to move in that period.

Conversely, an asset like gold has no anchor and is perfect for sustained valuation loops. It doesn’t have cash flows and is a perpetual instrument. Its price is its value, and its value is perceived to increase the more it rises. Does gold become more attractive if it falls 50%? Probably not for the vast majority of investors.

I think there are three broad groupings that frame an asset’s susceptibility to self-reinforcing valuation loops:

Strong valuation anchor: Most fixed income securities qualify for this group as they have contractual returns and a fixed maturity. Although when discussing quasi-perpetual assets like a ten-year US treasury the anchor is far weaker.

Weak valuation anchor: Equities reside here. Although they do have cash flows and a ‘fair value’ can be estimated, they are perpetual and have no (hard) limits on the theoretical future cash flows that can be generated. There is not much to prevent fantastical stories being used to justify either very high or low valuations. There are, however, certain extremes where valuations start to bite – US equities might trade at 30x earnings and the rest of the world at 15x, but it is hard to imagine the US reaching 100x.

Many commodities would probably fit into this category also, not because of cash flows but because of competitive market dynamics.

No valuation anchor: Gold and crypto are the obvious examples and what I would call belief assets.** They are perpetual with no cash flow and no reasonable means of valuation. It is not that stories are used to justify a rising price / valuation, it is that the price is the story. This creates the potential for prolonged trends where a rising price serves to increase the validity of the asset, and it does so without any obvious anchor to a valuation level. This can be extremely attractive, but it is critical to remember that this exact phenomenon can also operate in reverse.

–

Antti Ilmanen of AQR recently wrote a piece suggesting that equity investors extrapolate while bond investors look for mean reversion. I think one of the reasons for this contrasting behaviour is the strength of the valuation anchor for each asset class. The weaker it is, the greater the likelihood of investors acting as if higher valuations are making an asset class more attractive (and vice-versa). There is nothing to get in the way of the stories.

—

* By the valuation becoming more expensive, I mean paying more for the same expected cash flows, not a situation where a higher valuation is due to improving fundamentals.

** This doesn’t mean you should not own these assets – some may have useful characteristics (gold has Lindy properties) – but they are inevitably high risk and come with a wide range of outcomes.

—

Joe Wiggins’ first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

This article was originally published by Behavioural Investment.