The railways made a rapid impact on Britain. It was only in 1830 that inter-city rail travel started with the link between Liverpool and Manchester, but by 1840, they, and the other four largest English cities (Birmingham, Sheffield, Leeds and Bristol), were all linked to London.

Trains offered substantial savings in time and comfort over coach travel. In 1836, Manchester was reached from London in 18 hours 30 minutes by coach, but in 1844, this was reduced to 7 hours 45 minutes by train.

When, in 1847, the Trent Valley line was opened, providing a service to the north-west which avoided Birmingham, the LNWR’s publicity pointed out that those needing to do business in Manchester or Liverpool and return to London the same evening would have 4 hours in Manchester rather than 21/4.

By 1850 it was possible to travel by rail from London to Plymouth, Holyhead, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen. Even in the 1830s the mainline railways north of London saw themselves as an end-on connecting system. Arrangements had to be made for through fares and rates and the subsequent sharing of payments on an agreed basis through the mechanism of the Railway Clearing House the inspiration for which was the clearing house servicing the City banks.

The first railways were dedicated to the carriage of minerals, but following the example of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway which attracted a surprisingly large passenger traffic, freight traffic was less important until the late 1840s. This was in part because concentration on first and second class passenger traffic proved remunerative, but also because it was easier to arrange for through traffic to other lines for passengers than for freight. Traffic managers were perhaps slow see the potential of freight, particularly coal, for which the canals and coastal shipping were substantial carriers.

However, by 1849, the LNWR had a contract with the Clay Cross Company to bring 45,000 tons per year to London, though it was two decades before more coal was transported to London by rail than by sea. Elsewhere railways developed an enormous traffic in coal which was widely used, domestically and industrially, as well as by the railways themselves and for locomotive firing.

The GWR had substantial long-range hauls from the South Wales coalfield to London and Birkenhead, the latter largely for the use of steamships. The Midland not only conveyed coal to other parts of its own network, but also to Peterborough for onward transmission to the eastern counties and to Kew for distribution by the London & South Western and South Eastern railways.

In the mining areas, numerous branches were built to serve individual collieries or groups, and particularly in South Wales more extensive lines were constructed, backed by the colliery owners, to convey coal to the ports, particularly Cardiff, for export. Products such as iron and steel demanded quantities of raw materials. In 1870 the carriage of materials for the making of pig iron represented some 32% of the total sums received by the railways for mineral traffic.

When the Staveley Company began to work its own iron ore in Northamptonshire, half a million tons of ore left the area for the company’s iron and steel plants in Derbyshire each year. Large brickworks grew up alongside railways and areas with the more suitable clays sent bricks long distances, for instance, from Accrington and Ruabon, and later from the Peterborough area and Calvert in Buckinghamshire. As the railways penetrated the quarrying districts in North Wales they carried large quantities of Welsh slate, a building material long transported by sea, to make slate roofs even more dominant.

The rising demand and the ability of the railways to transport food items led to new markets in London as the old Smithfield became inadequate. There was an extensive traffic in livestock, amounting to 3% of total goods traffic by value in the 1860s. By the 1880s, refrigerated vans had been developed which enabled New Zealand lamb to establish itself first in London and then throughout the country. New traffic was established with other perishable foodstuffs.

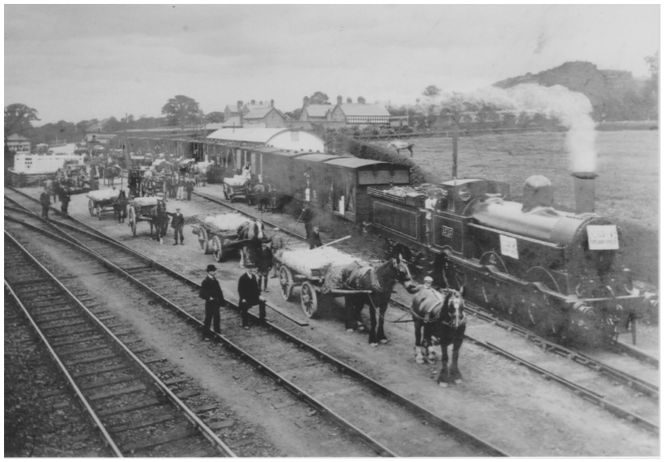

Loading Cheshire cheeses at Broxton, between Chester an Whitchurch.

In the 1830s, the Clerk of Billingsgate said that the working classes strongly disliked fish, regarding it as expensive and undependable in quality. Mayhew, 20 years later, saw it as the main ingredient of their diet due to its constant availability, and though much of it may have been dried or salted, the coming of special fish trains especially from Grimsby made fresh fish a reality for them. From the 1860s milk became an important cargo and, by 1890, 84% of London’s liquid milk was brought in by rail, with much of it coming from the West Country and the Midlands. There was a large traffic in fruit and vegetables. These developments contributed to a rise in living standards.

The railways also affected the country in other ways. The department stores were attracted to Kensington High Street by the Metropolitan railway station. Northampton lost its lead in shoes and boots to Leicester, partly because the latter was much more accessible by rail. Vauxhall Motors were attracted to Luton by its position on the Midland mainline. Rail was not the only reason why brewing was concentrated in Burton, but it was an important factor. Manchester became the headquarters of the Co-operative Wholesale Society because of its excellence as a distribution centre. Chivers, the jam manufacturer, developed his orchards at Histon, near Cambridge, as the village station was served by two railway companies.

Bulk conveyance of food, clothes and other articles meant generally cheaper goods, but a greater uniformity in what was available in shops throughout the country. As the mainline railways tended to converge on London, it meant some decline in the relative importance of provincial centres, exemplified by the overnight conveyance of newspapers produced in London to much of the rest of the country, and the triumph of railway time (Greenwich Mean Time) over local time.