Why can’t you afford a home?

UCL researcher Josh Ryan-Collins says it is due to inevitable landowner profits from land, to a majority of homeowners blocking fair taxation of those profits, and to excessive mortgage credit. His new book is not yet widely available, but he has written a long summary.

Causation is complex. Lawyers speak of ‘but-for’ causes; economists of ‘counterfactuals’. Things often have many causes, which can be necessary or sufficient in different combinations.

Ryan-Collins rightly asks questions about the banking system. For centuries, banks have received various implicit subsidies – too-big-to-fail status, deposit guarantees, lender of last resort facilities, exclusive access to reserve accounts, and maturity mismatches illegal in any other retail financial service – at a value and opportunity cost to the taxpayer of many trillions and without any serious check that we are getting value for money.

And it is certainly true that banks did far less mortgage lending in prior centuries. The peer-to-peer UK mortgage lending of the 1800s has been almost entirely forgotten.

He is right that easy bank financing and low nominal interest rates have driven up the price of housing, at least in some places. But, crucially, not in the places with a healthy supply.

A 2018 study by Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko showed a striking difference between two groups of cities. In cities like Atlanta, more demand and low interest rates were met with a jump in building new homes, while prices barely moved. In cities like San Francisco, the flow of new homes barely budged while prices vaulted.

In Cuba, cars are ‘unique’ and fixed in quantity because imports are prohibited. Second hand cars there rise in price, just like UK housing.

He is also right that private home ownership makes the politics of fixing housing far harder. Homeowners are happier when their house price goes up. Hence the tyranny of the majority, and the current explicit UK government target for house prices to continue to rise.

The 1950s upturn in his graph of global house prices coincides quite well with homeowners becoming majorities. Of course, it also correlates rather well with the introduction in 1947 of a ‘modern’ UK planning system without serious testing or any intention to facilitate large-scale densification of existing cities.

But his argument does not explain the experience of the UK in the 1930s, for example, when interest rates were low, de facto 100% mortgages became available and yet the working class were suddenly able to afford to buy homes in London because the Tube system enabled housing on land that used to be too far out. Meanwhile, landowners desperate to find something to do with their central London properties turned them into highly affordable mansion blocks with vastly more homes per acre, to tempt the middle classes.

There are crucial aspects of the microeconomics of housing that he glosses over.

If you are lucky enough to own a home in the south-east of the UK, the most expensive element is probably not the cost of building it. It is certainly not the land. It is probably the planning permission for that home to exist.

Land in the UK, even in the south-east, is surprisingly cheap if you eliminate the possibility of building on it – somewhere around £10,000 per acre.

You can test this in real life by knocking down a building, getting it designated as Metropolitan Open Land or green belt so that it can never be built on, and asking a surveyor to value the land for you. Or you can read the careful statistical studies that clever spatial economists such as Paul Cheshire, Christian Hilber, Ed Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko have done. (You will find that cheaper, if perhaps not easier.) Or ask a land promoter or planning consultant what they do all day and why.

Land is not, as Dr Ryan-Collins claims, unusual in economic terms in that it exists in a fixed quantity. So do aluminium, hydrogen, sunlight, seawater, and the number of hours someone can work per day.

Plenty of things exist in fixed quantities. They are examples of what economists call ‘inputs’. The story of the industrial revolution is of a vast increase in standards of living as we have learned to do far more with various inputs – for example, energy and even the weight of materials required for a product. For that reason, many products and inputs are far more affordable than they were.

Land does not inevitably appreciate in value over time. Agricultural land is far more affordable than in earlier centuries, because we have learned to produce more with it and to make better use of farmland in different places.

Land for housing is important not because of soil but because of location. A city of floating houseboats would experience many of the challenges of today’s land-based cities. So would a thirty mile high skyscraper on a small plot, or a future city in orbit. In some places it would be economic to live suspended from a helium balloon tethered above existing homes if you were allowed to. The hard thing is getting the permission.

Land supply may be inelastic, as he says – though not entirely, if you are Dutch – but land is only an input. We have a shortage of housing, not land, and housing supply is highly elastic in many places because, as with so many other things since prehistory, we have invented technologies to do more with a limited input: to add more homes on a particular piece of land. You know those technologies as staircases, chimneys, terraced houses, mansion blocks and lifts. Or you can look at them as creating more layers of land on top of one another, all in the same place on the map.

We have also invented technologies to substitute one piece of land for another. We call those bicycles, buses, cars, trains and videoconferencing. You cannot move land, but you can move people, or reduce the need for them to live near each other.

Some of the prettiest and most popular parts of many UK cities have literally ten times more housing per acre than much of the rest. We have vastly more scope to add more homes on existing land if we want to. There is no shortage of land at all. You could double the amount of housing, and double it again, and still have a prettier, fairer city. Do you really think homes would still be so expensive if we had four times as many? They would be affordable long before that.

To enable better outcomes, we need a better planning system.

He is right that planning systems did not suddenly become much more restrictive at the turn of the century. Tokyo actually allowed much more housing – which is why Tokyo became more affordable. But if you fix the total amount of housing allowed as many places effectively did a long time ago – and Los Angeles and Manhattan have actually reduced it – then housebuilding will increasingly bump up against that limit. Planning became more of a constraint over time, as Prof. Cheshire would put it.

If you want houses to be treated more like furniture, not speculative assets, then the obvious answer is to let people build many more of them, so the price does not rise inexorably. There is no speculative bubble in sofas.

People are not fools. Many want to own housing because prices have trended upwards for their whole lives.

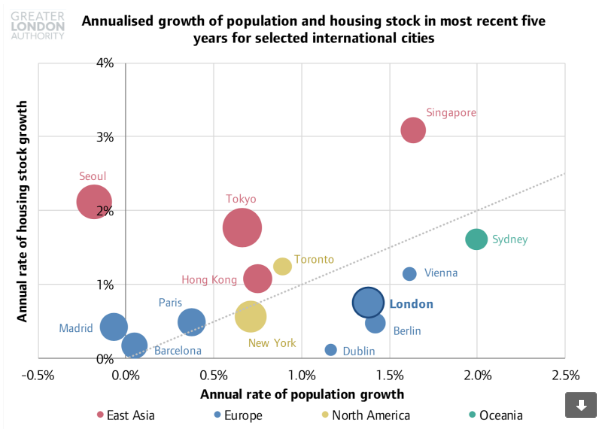

It is not ‘remarkable that house price-to-income ratios have been moving in the opposite direction in Western democracies and mature East Asian economies such as Korea, Japan and Singapore,’ as he claims. Those places have been building many more homes per head where it matters, as the GLA’s Housing in London 2018 report shows:

The people who publish regression analyses in high-quality peer-reviewed econometrics journals are unanimous that a better planning system would vastly increase the supply of homes and make them far more affordable.

How long can some ignore their evidence? Centuries probably. That’s why our campaign focuses on working with those with open minds to get real progress. Within twelve months after our first report, the core of one of our two main requests is now national planning policy.

The real question about housing, as he implicitly acknowledges, is what to do about it.

His call for political leaders to be brave is, sadly, exactly what housing campaigners have been asking for decades. It may excite your political base, but it will not help those in need, nor solve the feedback loop that keeps homeownership percentages high and entrenches political opposition to change. Political scientists have plenty of answers about how to achieve change, if you only ask them.

There is every reason to support sensible tax reforms. But most of the US has far higher annual property taxes on homes than the UK, and yet the US still has problems. Good luck imposing swingeing taxes not matched to cash flows on a homeowner majority. Even if you did, most people would still have less housing than they would like. Sensible tax reform will not end the shortage of housing, any more than taxing water in a drought.

And good luck weaning people off owning homes, as he suggests, without a credible promise that homes will stop getting more expensive.

No doubt we should look carefully at the banking system. But no change to that would ensure housing that is affordable as it could be.

Sadly, the final reason ‘why you can’t afford a home’ that he omits is that too many housing campaigners insist on their way or the highway. We would be far more powerful as a united coalition pushing for all the changes that would make a difference. Why not try to pull every lever we can?

We need to stop pretending that we have a shortage of land or that any of this is inevitable.

There are easy ways to improve the planning system that would lead to vastly better places and more homes over time. We could even do it without touching any pleasant greenfield sites, given a sufficient alliance to push through the right changes.

To deny the overwhelming evidence of the good that would come from a better system is to betray those most in need of help. We should work together to give people fair life chances, and plenty of truly affordable and beautiful homes.

Orignally published on CAPX.