Central banks hate shocks, but the shocks they hate the most are adverse supply-side shocks: the kind that simultaneously threaten to damage economic activity and inflict upward pressure on prices.

The US president is the personification of a supply-side shock, a one-stop shock machine. Despite the backtracking and the de-escalations, the US has unilaterally increased its tariffs on all its trading partners. Despite pushing to the front of the deal queue, the effective US tariff rate on UK exports has risen from 1% to 6%, according to estimates from Allianz Trade. On average, US tariffs are now roughly 15%, the highest since the 1930s.

However, the disruptive force of the Trump administration’s first 100 days reaches much deeper into the workings of the global economic system. The abrupt regime shift has prompted international investors to question the wisdom of their $16trn exposure to US equities. A sharp fall in stock prices between mid-February and early April has been largely reversed due to short-covering and more conciliatory language between US and China, but it is unlikely that the story ends there. The underlying motivation to reposition assets and de-risk portfolios is undiminished by the tariff climb downs. The hit to the external value of the US Dollar since the President took charge has seen Sterling’s value climb from $1.22 to $1.36.

And then there is the US Treasury bond market, the epicentre of the global financial system. The most highly regarded measure of Treasury market volatility is Merrill Lynch’s MOVE index. It uses an option pricing model based on a weighted average of option probabilities to reflect collective expectations for future volatility in the fixed income market. The tendency in recent episodes has been for the MOVE to raise its red flag before the VIX, the comparable indicator of equity market volatility. Anticipating the announcement about tariffs, the MOVE index jumped from 91 on 27 March to 140 on 8 April, the day before tariff increases above 10% were postponed by 90 days. Benchmark 10-year US Treasury yields plunged from 4.38% on 27 March to 4.01% on 4 April, only to surge again to 4.48% on 11 April, holding around this level in this level in mid-June.

It is not widely appreciated how fine are the tolerances of the global financial markets to these wild swings in government bond yields. Even a 50-basis point rise in yields from current levels could trigger extreme financial stress, embarrassing failures – remember Silicon Valley Bank in 2023 – and forced deleveraging in the banking and insurance sectors. Beyond the arithmetic impacts of pared-back tariff increases, the more significant threat arises from the fundamental reappraisal of the risks associated with US financial assets and the dollar. The zone of global financial instability lies closer at hand than the official reports would have us believe.

The first quarter of 2025 has flattered to deceive. As businesses sought to escape the impending tariffs, they accelerated their exports to the US. Over these three months, US visible imports soared by more than 30%, dragging down GDP growth in America, but supplementing it elsewhere. The recorded 0.7% improvement in UK GDP for the first quarter should be seen in this light.

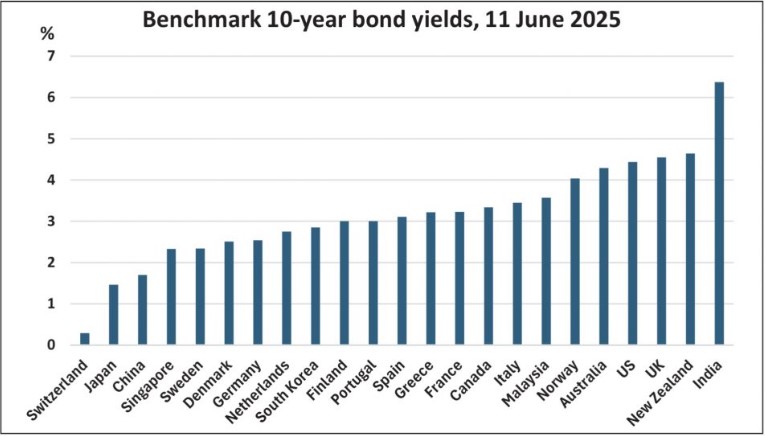

The Bank of England’s monetary policymakers face a dilemma. Superficially, economic growth is quite robust, and the inflationary risks are skewed to the upside. But the potential for negative impacts to business confidence, investment and trade, especially in the next six months, is plain for all to see. By adopting a calm and collected posture towards America, the UK government may be inviting capital inflows that will drive up the value of Sterling further still. However, by succumbing to various spending pressures at home, the budget deficit has ballooned to £152bn in 2024-25, equivalent to 5.3% of GDP, marking the UK out as a profligate sovereign. The cost of government borrowing, measured by 10-year yields, is even higher in the UK than the US (see figure 1, below).

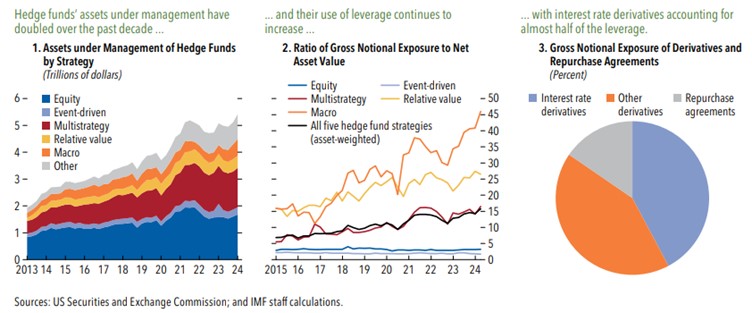

The force of leverage in financial markets interacts with the central bank dilemma. Figure 2 (below) offers a glimpse into the scary world of hedge fund leverage, courtesy of the IMF’s recent Global Financial Stability Report. Note that the asset weighted leverage of the $5trn industry has doubled over the past 10 years to 16 times net asset value. The greater is the perceived threat of economic recession, however short-lived, the more confident certain segments of the capital market will become that the Bank of England, among others, will bring interest rates down in hurry. And there are recent precedents to support this expectation, notably 2008-09. The Bank is facing another stern test of its resolve and its readiness to resist a tide of criticism. This time, it can draw some strength and inspiration from the Federal Reserve, led by Jay Powell, which is thus far standing firm.

Resisting the calls for urgent interest rate cuts in defence of an inflation mandate is standard fare for central bankers. , the Bank must remain alert to signs of fragility in the credit and financial system. Widening corporate spreads once functioned as the glands of the credit system, signalling financial stress.

Today, the weakest credits are to be found in the private credit sector, for which no prices exist. One of the worrying signs of latent financial distress has been the failure of government bond yields to take a lead from falling short-term rates – as happened last year. When sovereign bonds are unable to attract a firm bid then the potential for disorderly financial markets becomes apparent. Many governments have responded to the normalisation of short-term rates by curtailing the primary issuance of long-dated bonds. But the ensuing shrinkage of the duration of public debt in private hands must soon be arrested. The market must absorb a greater supply of the longer maturities.

The ultimate backstop to a bond buyers’ strike is the return of large-scale asset purchases by the central bank – commonly known as QE. When it comes to a showdown between the defence of the sovereign credit and the observance of the inflation target, the Crown wins every time.

This article was originally published in The Property Chronicle Summer Issue.